On Nov. 10, 2008, the national “Counterfeits Can Kill” awareness campaign rolled out with great fanfare. A joint effort from the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA); its nonprofit educational arm, Electrical Safety Foundation International (ESFI); and the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA), the program comprised an informational website and video testimonials from electrical industry luminaries. Its goals were simple: to bring attention to the glut of knockoff circuit breakers, cabling, and other products that had been penetrating legitimate supply channels in steadily increasing numbers for years — and to ultimately head off the hazards they can produce.

“We need consumers to be aware that these products are out there and that they can kill,” ESFI President Brett Brenner noted in a press release announcing the campaign. “Every day, more counterfeit electrical products enter into the United States undetected.”

He couldn’t have known at the time just how right he was. Not long before that announcement — maybe even as ESFI was interviewing manufacturers for those video testimonials — Elod Toldy was stepping off of a plane in China. This was no vacation for the Austin, Texas-based electrical distributor. After settling into his hotel, Toldy rifled through his suitcase, past the socks, underwear, and toiletries, to find the Stab-Lok circuit breakers he’d recently bought from American Circuit Breaker Corp. With them in hand, he set out into the maze of industrial plants to find a less-than-scrupulous manufacturer that would produce a couple thousand knockoffs — stamped with the very same Stab-Lok logo.

A numbers game

Virtually everyone in the electrical industry agrees that the counterfeit products problem is growing. It’s hard to find a contractor who hasn’t inadvertently bought something on the gray market that turned out to be a cheap impostor of the real thing or who knows someone who has. Yet no one knows for sure just how widespread the problem is. According to ESFI, circuit breaker manufacturers have lost $125 million in sales in the United States over the last five years. But that’s just an estimate.

And U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which, in effect, is the industry’s first line of defense, can only check a fraction of the nearly 25 million shipping containers that show up at its ports every year. Even when it conducts targeted inspections to confiscate counterfeits, as it did with 2011’s Operation Short Circuit, it tends to focus on consumer products. The three-month sting netted more than 139,000 items valued at nearly $6 million, but most were extension cords, batteries, and power chargers.

Complicating matters, as ESFI’s Brenner points out, is the fact that the people in the best position to help gather hard data — or at least make it possible for others — rarely do.

“Many times, when a contractor installs something and it fails, they’ll just assume it was faulty and that they got a bad batch of whatever product it was,” he says. “Maybe it was counterfeit, maybe it wasn’t. But they’ll swap it out for a legitimate one and move on. Unless they send that information back up the supply chain, the manufacturers and distributors will never be able to figure out where the problems are. That’s where, as an industry, we’re stuck right now.”

Part of the “Counterfeits Can Kill” initiative’s mission was to build enough buzz around the issue that the next time contractors discover they’ve bought substandard equipment they’ll know to alert someone — anyone, really — that something’s amiss. Yet it’s had the unintended consequence of goosing manufacturers to step up their game as well. Five years ago, Brenner says, many manufacturers shied away from addressing counterfeits publicly for fear of sullying their brand name.

“Most legitimate breakers are comparable from a quality perspective,” he says. “So a lot of electricians will say, ‘I heard Company X has reported finding counterfeit stuff, so I’ll just go buy from Company Y.” The irony with this logic, of course, is that Company Y may not have found anyone knocking off its product because it’s not looking.

Occasionally, there are those at the contractor level who do speak up. In December 2008, for example, an individual in Jacksonville, Fla., contacted U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) after suspecting that an order of Stab-Lok circuit breakers purchased from an eBay seller, Nick’s Sales, might be counterfeit. Upon examining them, American Circuit Breaker confirmed that they were, in fact, knockoffs, and ICE went to work investigating the seller. Nick’s Sales, an online offshoot of the brick-and-mortar Pioneer Breaker and Control Supply in Austin, Texas, also dealt in products from Connecticut Electric & Switch Manufacturing, Schneider Electric, Siemens, and ABB, which the feds had every reason to believe were counterfeit as well.

The next spring, armed with that knowledge, ICE agents established an undercover contracting firm in Florida, logged onto eBay, placed an order through Nick’s Sales for 11 Stab-Lok and Zinsco breakers, and waited.

Spotting the fakes

“Ten years ago, I didn’t worry that I wasn’t getting authentic electrical equipment,” says Michael Scherer, the general manager of Scherer Electric, which has served residential and industrial clients in western New York for 26 years. He’s worried about it now, though, because the danger in buying substandard products doesn’t come just from getting taken for a ride. At the end of the day, it puts customers at risk.

“If we put something in that was counterfeit, it fails, and somebody loses their possessions, a facility, or their life, that would be devastating to our reputation,” says Scherer. “And it would be devastating to me, personally, because I care about our clients. They’re friends and extended family of mine.”

There’s also the liability aspect to consider.

“The contractor and the distributor have a responsibility to make sure that what they’re buying is legitimate,” says Jerry Bowman, president of BICSI. “It’s easier for the distributor because they’re typically buying it from the manufacturer, unless they’re getting it on the gray market or from a third-party distributor. It’s not as easy for the contractor, especially if the distributor they buy from isn’t checking. But everybody in the supply chain is liable. They’re not relieved of that liability just because they didn’t know that what they got was illegitimate.”

How do you know what’s counterfeit? In the last decade, Scherer’s done his homework “I’ve been to tradeshows and seen the demonstrations that differentiate legitimate stuff from illegitimate stuff,” he says. And although he’s fairly confident he can tell what’s what, he admits that the differences between good and bad products can be subtle. “The weight may feel a little different,” he says. “Or maybe the handle tension on a breaker feels a little different.”

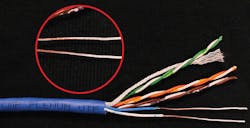

When it comes to cabling, another popular target of counterfeiters, the signs can be even harder to spot (Photo). “You’re not going to be able to tell by looking,” Bowman says.

Because the PVC used for cable jacketing burns like gasoline, it has to be treated with expensive chemical flame retardants. “So if I’m going to make substandard cable, I just make the jacket out of raw plastic and then put labeling on the outside that says it’s got the additives in there,” he says.

That makes having an open dialog with manufacturers — when possible, at least — so important. ICE officials had already opened those lines of communication when they received the breakers they ordered from Nick’s Sales in May 2009. So it didn’t take long to confirm that what they’d received was counterfeit. As the investigation continued, agents connected Nick’s and Pioneer Breaker and Control Supply to Elod Toldy, and with the newly acquired evidence in hand, they began to tighten the net around him.

Consider the source

So what exactly do you do if it’s virtually impossible to spot a fake? Scherer says he’s never knowingly purchased counterfeit breakers or cabling — there was, however, the 3M electrical tape that turned out to be “MMM” brand tape, which he bought from a shady dealer who’d cold-called him — and he chalks that up to a simple, straightforward policy: “We deal with local vendors and national supply houses that we know.”

ESFI’s Brenner and BICSI’s Bowman agree that the best — and only — way to avoid purchasing counterfeit products is to stick to trusted sources. Because the buck ultimately stops with the outfit who installs the equipment, it’s on

contractors to do their due diligence. Of course, sometimes that’s easier said than done. Consider the gray market. There’s nothing inherently wrong with buying surplus product from another contractor who has a solid reputation. But what if that outfit cut corners just this one time, bought from a distributor that either wasn’t aboveboard or — again, just this one time — didn’t source its inventory directly from the manufacturer?

“It’s situations like that, where you have multiple levels of distribution, where you run into problems,” says Brenner. “Even if you’re not purchasing directly from them, if your product is coming from online distributors that don’t do a very good job of sourcing where the product is coming, that’s how this stuff penetrates the market.”

Online sales have, without question, exacerbated the counterfeit problem. A quick search of eBay for circuit breakers yields more than 150,000 results. Go to Amazon.com, and you’ll find more than 71,000 items to choose from, sold either by Amazon itself or affiliates with which it contracts.

“I have a real problem with that,” says Brenner. “Because who’s to say that whoever’s vetting — if anyone is, for that matter — the buyers and sellers in the electrical distribution business has any clue what they’re doing?”

It’s only fitting, then, that it was an online deal that brought down Elod Toldy. On April 21, 2010, ICE agents searched Pioneer Breaker and Control Supply’s warehouse in Austin and found more than 20,000 counterfeit electrical products. A second search at another of Toldy’s facilities netted 77,000 illegitimate breakers. All told, the items had a retail value — had they been the real deal — of nearly $5 million.

Toldy, a 63-year-old émigré from Hungary, cooperated with authorities and admitted to contracting with Chinese manufacturers to produce the substandard products for a fraction of what their legitimate counterparts would have cost him. He’d even acquired counterfeit UL labels — the search of his second facility uncovered 60,000 of them — that he used to further the scheme. He was charged with one count each of mail fraud and trafficking in counterfeit goods. In November 2012, he was sentenced to one year and a day in federal prison and ordered to pay nearly $60,000 in restitution to his victims.

Toldy’s case is the first and only successful federal prosecution of a seller of counterfeit electrical goods in the United States. And although he operated as a distributor, his story serves as a valuable lesson to contractors as well. Prior to sentencing in November 2012, his attorney made the case that Toldy had for years been an aboveboard distributor of electrical components, many of which were after-market replacements for parts discontinued by their original manufacturers. But as the economy began to soften in the late 2000s, he searched desperately for ways to save his business and ultimately turned to counterfeiting. It was a position that many contractors found themselves in during the Great Recession, as jobs dried up and revenues fell. As they looked for ways to stop the bleeding, they made themselves vulnerable.

“I don’t think anybody goes out looking for counterfeit products,” says ESFI’s Brenner. “Everybody’s trying to shop and get the best bid possible to win jobs. What’s happening is contractors are trying to cut every corner they possibly can to win a job. And when they’re doing that, they’re sourcing product that might be questionable at best.”

That’s a risk Michael Scherer isn’t willing to take. “If we put something in, if we don’t know where it comes from, how do you warranty that item? Now we become responsible for the warranty of that particular item,” he says. “If it fails in the negotiated time that you warranty it, everything you saved on it you’ve just lost — probably 10 or 20 times over. I just don’t see what the upside is.”

Halverson is a contributing writer based in Seattle. He can be reached at [email protected].