Partnering with Electrical Distributors for Improved Efficiency

What do Amazon, Apple, Disney, Google, Harley Davidson, and Microsoft all have in common? These are just a few of today’s power house companies whose humble beginnings were born out of a garage. Like these business giants, many electrical contracting operations can trace their roots back to similar starts. The garage is not only a safe haven and “low-capital” startup for business, but it can also serve as a space to build products or equipment prior to taking it to the job site. It’s also not a bad place to store stuff.

As the business grows, shelves are added to try and keep product inventory organized. Leftover items from previous jobs also start to make their way back into the garage. Before you know it, you’re in the business of material handling and logistics. Although this model can work for a while, it tends to break down once the complexity, speed, quantity, and size of projects increase. When this happens, it’s time to rely more on product suppliers for help. In fact, it’s time to look to the entire host of experts in the logistics and supply chain and use their capabilities to the fullest.

Construction is facing a major shift toward the concept of industrialization. As it happened in other industries, industrialization follows these steps:

- Management of labor

- Management of work

- Lean operations

- Modeling and simulation

- Feedback from the source

Industrialization begins with management of labor and work, including identifying who should do what, when, and where. In other words, it doesn’t all have to be done on site as the schedule suggests. Using vendors to support the work — not just sell material — is one way to accomplish this.

Evaluating efficiency

Even though electrical contractors constantly fight for the lowest material price, in reality, price is secondary (see Lowest Installed Cost). Without the lowest prices — and often even with them — contractors are unable to recover from the labor losses associated with handling materials instead of performing installation work. MCA’s research, published in a prior EC&M article (see “Real Ways to Reduce Material Handling Costs” in the January 2008 issue or on ecmweb.com), shows that field labor spends 40% of their time on material handling. This includes material movement, ordering, receiving, returning, looking for, sorting/organizing, and more. To quantify the true cost of these activities, let’s look at a simple example.

Assume a particular job site is running with 10 electricians. Its inventory consists mostly of anticipated commodity items (the project manager ordered 80% of the material identified on the estimate at the start of the job; however, the estimate was not broken down to a fine detail nor reviewed by the foreman who is running the job). Therefore, each day a small shipment of miscellaneous items is required to keep things moving effectively and match the work environment. Additionally, let’s assume that most, but not all, of the deliveries are received as expected and as ordered — and that the loaded cost for labor is $40 per hour.

If inconsistencies and last-minute changes to the order cause interruption and realignment of workers at the job site, resulting in a loss of productive effort equal to one hour per week per man, then this can be used as a basis for calculation. One hour per week per man is simply allowing 12 minutes per man each day to finalize whether he will be working on his primary plan, alternate plan, contingency plan, or emergency plan — and allowing him to gather the correct material to get started.

One hour per week, per man (12 minutes per day per man), for a 10-man crew at $40 per hour equates to: 1 hr/week/man × $40/hr × 10 men × 50 weeks/year = $20,000 per year in lost productivity

And that’s just on one project!

This same example can be expanded to measure the entire company. If the company employs 200 electricians at $40 per hour, then the resulting cost of lost productivity is $400,000 per year.

Compare these costs with the savings you may receive on the same project for a “good material buyout.” Let’s assume this 10-man project is a $250,000 project, and with a good buyout, there was a 2% savings on material price. If material represents about half of the project cost, in a best-case scenario, the savings is around $2,000. However, this savings is burned up in a few weeks by losing time on material handling. You can do this calculation for your own company, and ask yourself what material and logistics items are eating up that one hour.

Establish a vendor partnership

To combat labor wastage on material handling tasks, you should select suppliers based on what they can do to provide the correct material, at the specific installation location, at the time the labor is ready to install it.

Choosing a vendor based only on material price alone is not going to reduce material handling costs, though. If the goal is to reduce job-site material handling, then the cost of the material is far less important than the effective use of labor. Contractors need to ask suppliers what they can do to provide the correct material, at the right installation location, when labor is ready to install it.

Following is an outline of the various levels of service vendors can provide at different commitment levels:

Non-partner, preferred service provider

- Provides vendor managed inventory (VMI) and other value-added services generally associated with unique lighting, gear, or other packages.

- No purchase commitment beyond the individual service.

- Contractor responsible for all productivity improvement.

Descriptive partner

- Provides value-added services for a complete project.

- Project level purchase commitment in return for shared accountability to project productivity.

Selected partner

- Limited number of partners actively participate in all aspects of all projects of the company.

- Large scale multi-project purchase commitments, including commodity items in exchange for shared accountability for both project productivity and company backlog.

The process of selecting a full vendor partner can take up to six months, and should be done very carefully and deliberately. Below is a brief overview of the steps that need to be taken, based on MCA’s research and work with electrical contractors across the country.

Define vendor requirements

- What are the business objectives?

- What are the operational objectives?

- What are the functional requirements?

Evaluate the vendor partnership

- Gather team input on services

- Can candidates provide the service?

- Have they provided the services before?

Develop a short list

- Analyze strengths, weaknesses and opportunities

Gather detailed input on what all parties want for various aspects of partnership

- Vendor partner presentation

- On-site visits

A material logistics solution is most effective with a vendor partner who is willing to take equal risk in developing solutions for mutual benefit of reducing project cost. It can also be attempted with material and equipment suppliers who have pre-developed solutions from their learning with other partner contractors. The Figure below shows a sample work cube, where project tasks are broken down and identified by the electrical contractor’s foreman.

A valuable vendor partner will learn the project through the eyes of the project team and begin planning possible solutions for reducing cost. Some solutions could be predetermined, such as:

- Preassembly of selected components

- Wire cutting and paralleling

- Testing of equipment

- Kitting and packaging in job packs suitable for installation

- Staged deliveries to the job site; delivering as the material is needed

- Stocking and maintaining on-site boxes and trailers for commodity materials

- Material returns processing

- Job site material clean-off

- Specification verification

- Submittal preparation support

- Receiving, inspection and damage claims support

- Off-site storage at the vendor’s secure warehouse

Other solutions can be created for project-specific risks and needs. For example, Photo 1 shows a delivery method specified for a project — where the material can be called for from the crew per floor and area of the job site and delivered to those dedicated crews.

These (and other) services are identified through a dedicated procurement planning session, including the electrical contractor’s project team (project manager, superintendent, foreman, procurement manager) as well as the vendor’s team, which needs to go beyond the salesperson. The solutions come from reducing risk at the point of installation. The more parties are involved in planning, the more solutions are possible and the higher likelihood they will come off without a hitch.

Another example (Photo 2) shows an area of the job site for consistent delivery of prefabrication material, picked up from the contractor’s shop by the vendor as requested, along with other commodity items flagged and color coded to go along with the same phase of installation.

Some contractors and vendors may look at these simple examples and say “we already do that,” “we have better carts available,” or “we do that better by using QR codes.” The part that is not visible in the two photos, which is more valuable than the QR codes, is how the project team came to these integrated solutions, which is through all of the processes, including vendor selection described above.

Over the past several years, an increasing number of contractors have been successfully working with their supplier partners to achieve the goal of reduced lost time from handling material. The overall results of these efforts have been to improve productivity and profitability by striving to deliver complete projects at the lowest installed cost. The distributor’s advantage in these partnerships is also higher profits and more secure sales. Smart suppliers have seen a major benefit in partnering with contractors and are adding contractor partnership offerings to their strategic planning initiatives.

Daneshgari is president and CEO of MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. Moore is vice president of operations. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

SIDEBAR: Lowest Installed Cost

Lowest installed cost does not mean cheap. In fact, paying more for the material can actually improve a contractor’s profit margin.

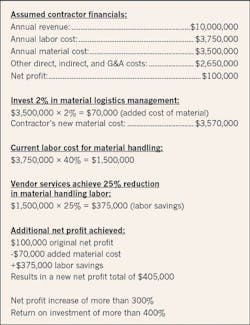

The basic premise of lowest installed cost is that a contractor can manage the trade-off between material cost and labor savings to provide greater value to the customer, greater sales to the supplier, and greater profits to themselves. Another way of viewing this is the return on investment in vendor services. With an efficient partnership, based on mutual understanding of each other’s business needs and operations, finding a win-win solution is not only doable, but also almost unavoidable. The calculation below shows the return on a modest 2% investment in material price resulting in a willing vendor partner helping the contractor to reduce material handling labor costs by 25%.

About the Author

Dr. Heather Moore

Vice President of Operations

Dr. Heather Moore is VP for customer care and support at MCA, Inc., as well as a well-known researcher and author in the construction industry. Dr. Heather can be reached at [email protected]. She is also part-owner of a WBENC-certified company, WEM, LLC, that provides logistics and scheduling services for the construction industry, as well as being the only licensed reseller of MCA, Inc.’s software products that are focused on Making Productivity Visible to Everyone®.