Study Reports Electrical Occupations on "Strenuous List"

Workers who labor in electrical occupations really do labor, according to new data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

A newspaper’s analysis of the BLS’s first-ever Occupational Requirements Survey places electrical workers high up on a ranking of the most physically demanding jobs.

Reporting on the survey and analyzing the data, the Washington Post concluded that electrician is the thirteenth most “physically demanding” occupation, followed closely by electrical power line installers and repairers in sixteenth place. The Post based its ranking on scores BLS generated from its survey for specific physical “stressors” workers in thousands of occupations routinely encounter, such as climbing, pushing/pulling, reaching out/down, reaching overhead, and low posture.

On a 0-100 scale of increasing demands the Post created to interpret the data, electricians had a median score of 42 and power line installers and repairers a score of 40 for all stressors combined. For comparison, the top spot went to firefighters, with a median score of 82. Installation, maintenance, and repair workers, a broad category that electrical workers might fit into, had a score of 63. Jobs as disparate at roofers, telecom installers, law enforcement officers, and RV service technicians occupied the top 10.

In another category the Post developed based on the raw data, power line installers and repairers ranked 10th in jobs requiring heavy lifting, with an average maximum weight they must lift or carry coming in at 66 pounds. Firefighters topped the list, averaging 126 pounds.

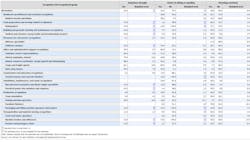

In other measures of physical demands on workers, power line workers are much more constrained than average on the choice of whether to sit or stand when working and far more exposed on average to reaching overhead. Ditto for installation, maintenance and repair and construction and extraction workers (see Figure).

In one of the six occupational requirements areas BLS focused on in its 2023 survey — environmental conditions — these workers also scored much higher than average on measures of exposure to heights, a major injury risk factor.

In its news release announcing the survey results, BLS chose to highlight specific findings about work pace, apparently deeming that a major contributor to job stress. It found about 39% of all occupations require a “generally fast work pace.” Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations generally and power line workers specifically came in slightly below that average while construction occupations came in with an above-average 46% reading.

The BLS survey may provide more food for thought for contracting, construction, and industrial sectors struggling to find electrical workers. While there’s scant latitude for employers to alleviate the inherent physical demands of the electrical jobs as they’re performed today, awareness of the barrier they could present might be important.

There’s some evidence that physically demanding jobs can force workers into early retirement, a problem the construction trades generally are confronting. A 2022 report on the status of older workers by the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis cites a 2021 study that suggests increased physical demands on the job are associated with a 10% greater probability of being retired. While job loss is a chief reason, the center says “involuntary retirement is also driven by health issues, such as those brought on by working in physically demanding jobs. For example, the National Academy of Social Insurance estimates that in 2012, more than eight million older workers were forced to retire earlier than anticipated due to health problems.”

At the other end of the spectrum, it’s an open question whether younger workers employers need to recruit into the electrical trade to replace aging workers and fill newly created slots will be put off by the prospect of physically demanding work. Data on that question isn’t abundant, but buzz about “slackers” among the Gen Z cohort industry will need to court may be cause for concern.

A 2023 study by Soter Analytics, a global safety company for manual workers, found one-quarter of Gen Zers polled thought industrial work was not safe. That might reference factory-type work, which does employ electrical workers, but could be interpreted as a broader statement about views on construction and other blue-collar work generally.

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].