Making Change Management Simple

Managing a construction project is like navigating a road trip with detours, bad weather, and a destination that changes mid-route. You know the direction you need to go, but constant changes must be addressed.

When you are on the job site, you may feel like you are the sole navigator, dealing with the roadblocks and new requests from the general contractor (GC) as they come up. But this is usually not the case. You have project team members to support your efforts. Open communication with your project team is critical, so when you do need to pivot, you can make an informed decision that lets you remain in control of your project.

Clinical research done by MCA, Inc. indicates that a typical construction project will see 30% change orders. Gaps in visibility depend on your level in the company and your ability to anticipate change orders.

Managing money, manpower, and material can be challenging when it comes to change orders. Some may be fairly obvious, depending on who you are, where you’re working, and how they’re communicated. The link between work and money is not always connected and easily managed. While you may know it’s different “work,” are you able to bill for it? Conversely, sometimes there are change orders that you have funds for that may not match the work that needs to be done.

Visibility of change orders

If you’re on the money side, when do you find out? You might be the last to know. It depends on your internal processes for managing change orders. It could be:

- When an input change is pending (i.e., the project team has sent it out for a quote).

- When it’s approved (i.e., when the customer sends the official change order back).

- When the job has unusual behavior (typically a fade), which prompts the team to think through whether they should put in change orders to cover the fading material or labor estimate.

If you’re a project manager or work in the office, you may hear about change orders in a few different ways and usually when your GC/customer needs something officially.

- Receiving a proposed change order (PCO) — customer/external request.

- Other communications, such as a verbal request, RFI, construction bulletin, or supplemental instructions.

- Weekly job review meetings.

In the field, your foremen/lead may see or hear based on impacts and fast items that they’re adapting to at the job site, such as:

- Revision of a print or answer to an RFI.

- Customer is talking with them (e.g., GC, owner’s rep).

- Project manager talking to field lead throughout the week (phone call, text, email), letting them know what they’re hearing.

- Weekly job review meetings — when you see that there is a productivity loss that can’t be explained within the current work scope.

- Updating observed percent complete, and realizing there is missing work, or extra work not in the original plan.

- Other trades (hear of a change that was sent to someone else, but you haven’t gotten it yet, or they’re back in a place that you thought was done).

These change orders can be the most difficult to capture in the office as the field teams are making many decisions each day to keep the jobs moving forward, and, in many cases, the office has no idea, according to Dr. Heather Moore's 2013 dissertation, "Exploring Information Generation and Propagation from the Point of Installation on Construction Jobsites: An SNA/ABM Hybrid Approach." Tack on those things that happen that you may not connect to an official change order. Sometimes it’s the things you DON’T see that you’d like to know about in advance and get documented. Key areas of scope creep or change orders needed include:

- Trade stacking — leading to delays.

- Schedule impacts — requiring work changes.

- Temporary power — adjustments not in the initial scope.

- Out-of-sequence work (less effective manpower plan, working over finishes, etc.).

- Multiple passes (go-backs) for a variety of reasons.

- Changes to job-site logistics (parking, lay-down, lifts, etc.).

We hear of the changes, but what can we do about them?

The key is to get things out of your head and into an easily accessible single point of entry log. Thinking about change orders as a change in money and scope that you let the field know is coming is different than thinking about changes in work that need to be followed up with money for the defined scope. Two-way communication is key.

If you are leaning on products that use the ASTM Standard for Job Productivity Measurement, like Agile Construction® tools and/or JPAC®, you may look out for dips in productivity (lasting longer than one to two weeks), which can result from work completion that is not accounted for in the existing work breakdown structure (WBS). An example of a work breakdown structure for fire alarm installation is shown in Photo and discussed in a recent EC&M article, “Planning Job-Site Lighting Installations.” With your WBS as a reference, you can ask, “What are we doing that’s not in the base scope?”

During your weekly job review meetings or observed percentage complete updates, if the field lead on the job finds there is work that is not in the WBS to score, this is another indication that either scope was added since the original plan was created, or that we missed breaking down the work in the WBS. If you didn’t initially create a WBS, start one from wherever you’re at, and document what work is left to do. Make a work plan that the team can refer to and discuss. Explicit plans can be easier to review.

Having a way to quickly document changes from all of the sources listed above, to make things visible for action, is what’s needed. It needs to be simple, fast, and immediately captured. Electronic capture is best in a system that can log and categorize for future use. Whether you decide to bill for the changes or use them in negotiations and discussions, having data at your fingertips is key. Noting it in real time will save you time down the road.

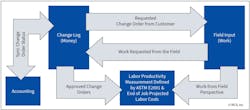

The Figure depicts how this information should flow between the field and office for change orders when there is a system in place to ensure timely communication. The project manager passes along change orders from the customer to the field, and the field passes along work requests as they are presented on the job site.

This two-way communication between your office and the field is critical. It’s also key between you and the other trades and the GC.

Here are some suggestions on how to use the information:

- Keep talking to the GC (it may take more than once, and likely will require backup).

- Keep talking to the other trades, sharing what you know, and appreciating the situation you’re all in.

- Don’t do the requested work immediately; meet with the GC to arrange for a separate team to handle the task, so the core team can stay focused on their work.

- Begin highlighting potential issues early on. Emphasize that any impact on electrical will affect all trades (adopt a positive approach).

To effectively deal with those change orders that will come, you have to:

- Recognize that small changes add up.

- Document them quickly in a single point of entry log.

- Know that small PCOs add up (>3 hours at a time).

- Catch items as early as possible, and report that there is a possible impact on drawings/contract documents.

- Put “potential” change orders on the log.

- Use the information to decide how to approach your customer.

About the Author

Sydney Parvin

Sydney Parvin is associate data analyst at MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. She can be reached at [email protected].

Jennifer Daneshgari

Jennifer Daneshgari is the vice president of financial services at MCA, Inc. She can be reached at [email protected].