Electrical Power Design Considerations for All-Electric Hospitals

Key Takeaways

- Redundancy in power sources, including multiple utility feeds and paralleling generators, is crucial for ensuring continuous operation during outages.

- Proper load assessment and equipment redundancy planning help optimize emergency and normal power capacities, considering future expansion needs.

- Designing for multiple power sources and implementing fail-safe distribution strategies minimizes single points of failure in critical systems.

- Fuel capacity planning, including extended runtime and fuel polishing, is vital for emergency preparedness in all-electric healthcare facilities.

Electrical power design in hospitals is one of the most critical aspects of facility engineering. Reliable power ensures life-saving equipment, lighting, HVAC systems, and critical services always remain operational. The basis of design for a standard 100,000-sq-ft hospital includes:

Departments. This may include surgery, sterile processing, laboratory, pharmacy, imaging, emergency, intensive care unit, labor and delivery, medical-surgical patient rooms, and support spaces for every department.

Space heating. This is achieved by using condensing boilers with hydronic piping throughout the facility. Cooling is achieved by using air-cooled chillers with hydronic piping throughout the facility. Humidification is achieved by electric steam generators.

The complexity of this task increases significantly when the hospital relies entirely on electrical utility services.

The trend to eliminate or reduce the use of natural gas is growing due to a combination of environmental, economic, and policy-driven factors. Whatever the reasons, engineers are tasked with delivering the same functionality of a traditional hospital without the use of natural gas. For electrical engineers, this includes utilizing the electrical service for all HVAC heating, domestic hot water heating, and any steam generation needs.

This article discusses the key considerations, initial load assessments, and best practices in designing robust, code-compliant, and resilient electrical power systems for all-electric hospitals with utility and generator-only power infrastructure.

Communication, communication, communication

As with anything new or unique to a project, success begins with great communication. In this case, early communication with the building owner and the design team is critical so all stakeholders understand the differences between an all-electric facility and a traditional natural gas facility.

Many owners already maintain an existing facility or several facilities, so it’s important that you inform them of how an all-electric facility is different. For an end-user working in an all-electric hospital, there is little to no direct impact on the everyday tasks and needs of staff and patients. The largest impacts fall on facility management departments and emergency planning personnel. Those are the key players who need to be at the table early in the project’s concept phase.

Since central steam systems and their distribution simply don’t exist in all-electric facilities, there should be a larger presence of electrically focused personnel on staff. This bodes well, given that electrical distribution takes on a higher level of importance — potentially incorporating alternate electric utility circuits or paralleling generator setups to increase redundancies. Most existing facilities already use multiple electric utility sources and paralleling generators; therefore, they have experience with those systems. For those new to paralleling, advances in paralleling technology have made that option simpler and more cost-effective than ever before.

Emergency planning is particularly crucial for all health care facilities, and many resources are devoted to this task alone. The key is that facility managers must understand the redundancies. Traditional facilities utilize natural gas and fuel oil as redundant energy sources for boilers and hot water heating. In an all-electric facility, all redundancies come from electrical power sources from the local electric utility as well as on-site power generation, typically in the form of diesel-powered generators.

Preliminary load estimation

Now that the owner is comfortable with an all-electrical design, it’s time to determine preliminary load estimates. The total normal demand load service size in VA/sq ft (volt-amps/square foot) for all-electric hospitals is typically in the 32 VA/sq ft to 40 VA/sq ft range. This range will differ based on your engineering judgment regarding load classifications and load factors applied to those classifications. Total emergency service demand load size will be in the 16 VA/sq ft to 20 VA/sq ft range.

As with any hospital project, you’ll be discussing what specific departments the owner would like to include in the emergency system. However, in an all-electric hospital, there is another layer that involves additional discussions with plumbing and mechanical engineers. The primary objective is to understand their equipment redundancies and what is required to be on emergency versus normal.

For example, if the condensing boilers are designed in an N+1 configuration, where two boilers meet the design load, and one boiler is redundant, not all three boilers may need to be fed by emergency power. In addition, if the boilers are controlled such that only two of three can operate simultaneously, only include two boilers in your load calculations.

The same is true for chillers, hot water heating equipment, and the associated pumps for each system. Continue to apply the same logic for electric humidification. Decide with your design team where humidification is required to be on emergency and apply those loads as required. It’s important to go through this exercise with the owner and design team to ensure proper service and emergency service sizes.

Sources of power

As mentioned in the introduction, all redundancies come from electric sources, so it’s imperative to limit single points of failure as much as possible. In an all-electric facility, it’s ideal to campaign for multiple electric utility sources for the normal service. These options will come directly from the electric utility, so get them engaged as soon as possible.

Most electric utilities are pleased to provide a single-circuit service and a single utility-owned transformer to the customer. Anything above and beyond typically requires negotiation and owner funding to achieve. Use the influential parties involved as needed.

In general, municipalities and the public at large desire a stable health care facility, so support can be gained by engaging several stakeholders. It’s also worth reminding the electric utility that they will benefit from selling the owner the only electric utility source to an all-electric facility.

Research any available rebates for an all-electric facility and even the possibility of paralleling the electric utility feed with the hospital’s emergency generators during peak demand windows. Potential solutions for normal service may be two electric utility circuits from two separate feeders, terminated in switchgear to operate in a main-tie-main configuration. Another may be as simple as getting two electric utility circuits from separate feeders, terminated in a single switch that can transfer between either source. Anything that can be done to limit the distance or the use of a single feeder into the facility is beneficial to surviving a normal power outage.

As with the normal sources previously mentioned, the emergency sources must be redundant as well. Don’t limit the emergency source to a single generator. In most cases, this will not be an issue due to the increased emergency demand load of an all-electric facility, in which a single generator becomes too large and impractical.

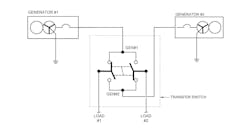

Traditional multiple generator setups can be as simple as using multiple source transfer switches (Fig. 1) to utilizing main-tie-main switchboards with the tie normally open, and both sources separately feeding loads, with the ability for one source to feed all loads. This is a simple, cost-effective solution with a proven track record. It is also a good option for facilities when their personnel are hesitant or unfamiliar with paralleling systems.

As just mentioned, paralleling generators is another option to consider. Paralleling generators are designed to operate together and tie into a common bus to act as one source for the entire emergency system (Fig. 2). Traditional paralleling systems utilize large paralleling switchgear (UL1558) with logic controls within the gear or in separate cabinets.

Thankfully, if desired, manufacturers have been able to add paralleling systems into switchboard (UL891) construction, reducing cost and footprint. Additionally, on-board paralleling is another option in which all generator paralleling logic is contained within the generators themselves, and the emergency switchboard becomes a typical switchboard without any electrically operated breakers.

The advantages of paralleling cannot be overlooked. There are options at every price point, and the largest advantage is scalability. Many facilities have master plans of future expansion, and paralleling is the easiest method for adding generators in the future as expansion takes place and demand load increases. Paralleling controls also utilize human-machine interface screens to allow the user to actively see how the electrical power system (EPS) is operating, and can also provide logging and monitoring when testing monthly and annually as required by NFPA 110, Standard for Emergency and Standby Power Systems.

Fuel capacity is another factor that increases in all-electrical facilities. Simply put, larger generators consume more fuel. NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, and NFPA 110 do not specifically dictate fuel supply requirements for Type 10, Class X, Level 1 generator systems, but rather defer that decision to the local authorities having jurisdiction (AHJ).

However, most AHJs will default to 96 hr for a couple of reasons. First, the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) recommends a storage capacity of 96 hr for facilities in areas that are likely to experience extended power outages with a minimum requirement of 24 hr. Second, 96 hr aligns with The Joint Commission’s requirement that hospitals must have an emergency management plan for the first 96 hr of an emergency. This does not dictate that the fuel supply provides 96 hr of runtime, but that facilities know what to expect and how to handle all operations.

Another conversation to confirm with the AHJ and the owner is the runtime of fuel supply at a percentage of generator output. Generators naturally consume less fuel at 75% load than they do at 100% load. You’ll quickly discover that a generator consuming 75 gal of fuel per hour requires 7,200 gal of fuel to reach 96 hr just for that single generator.

NFPA 110 also requires the total capacity to be 133% of the code-required runtime capacity, pushing this amount to 9,596 gal. This additional 33% allows for several rounds of testing for maintenance before the fuel level reaches its minimum level to provide the full required runtime.

It’s possible to provide this amount of fuel in a sub-base tank mounted under the generator. However, it necessitates a custom tank. Due to the large capacity, the tank itself rises three to five feet above grade, with the generator sitting on top. At this height, you need to use raised platforms or catwalk structures to access the generator.

The other solution is a fuel storage tank either above or below grade. These systems introduce pumps, controls, alarms, and potential secondary containment requirements. All these complexities need to be communicated to the owner and design team, as many facilities have not experienced this much fuel on-site. Fuel-polishing, whether a permanently installed system on-site or a contracted service from a mobile system, is highly recommended.

Another design feature to consider is a combination load bank and temporary generator connection cabinet. NFPA 110 requires initial start-up testing, monthly testing, and annual testing at various loads on the generator. Many facilities encounter months where their testing does not meet the 30% load of the nameplate rating of the generator. In those situations, load banks must be used to achieve the desired load. The connection cabinet provides a method of connection for a mobile load bank.

When sizing and designing the emergency power supply system, consider these minimum load requirements for testing so an estimate can be achieved without a load bank. This same cabinet can be configured to allow a mobile temporary generator to connect to the emergency supply system. When using a single generator, NEC Sec. 700.3(F) requires a permanent method for connecting a temporary generator. While this is not required when multiple generators are in use, it is another feature that ensures you have a redundant source if failures are experienced with the permanent emergency power source.

Distribution

When it comes to distribution, consider points of failure and options to eliminate single failure points. Traditional strategies include main-tie-main switchboards, allowing one side to feed another in maintenance or failure situations. Another is connecting switchboards fed by two different sources from bus to bus using interlocked circuit breakers to create a redundant path. You’ll also find that due to additional large heating loads once you’ve added to the equipment branch, you’ll most likely need to employ multiple transfer switches to divide up the loads in a practical manner. Always keep the owner in mind. All owners want a certain level of redundancy, but not a system so complex that it requires unnecessary education and expense to operate.

Key takeaways

An all-electric facility is an exciting challenge for an electrical engineer. Designing electrical power systems for all-electric hospitals is a complex but increasingly vital task as health care facilities transition away from fossil fuels. Successful implementation starts with early and thorough communication among all stakeholders, especially facility managers and emergency planners, to align expectations and understand operational impacts.

Redundancy is paramount. Thoughtful distribution design that focuses on minimizing single points of failure without overcomplicating operations is the goal. Simplicity, scalability, and reliability must be balanced to deliver a power infrastructure that meets the demanding needs of modern health care.

In the end, the transition to all-electric hospitals represents not only a shift in energy sources but also a fundamental rethinking of health care facility engineering. With the right planning and design strategies, electrical engineers can lead this transformation — delivering sustainable, resilient, and future-ready hospitals.

Basis of Design

This sidebar outlines the electrical power demands and system strategies for an all-electric hospital project.

- 100,000-square-foot hospital.

- Departments include surgery, sterile processing, laboratory, pharmacy, imaging, emergency, intensive care unit, labor and delivery, medical-surgical patient rooms, and support spaces for every department.

- Space heating is achieved by using condensing boilers with hydronic piping throughout the facility. Cooling is achieved by using air-cooled chillers with hydronic piping throughout the facility. Humidification is achieved by electric steam generators.

About the Author

Joe Levin, P.E.

Joe Levin, P.E., is a health sector senior project manager at Henderson Engineers, a national building systems design firm.