First, the good news: Despite the pandemic, the U.S. solar market grew by another 3.5GW in Q2, with 71% coming from the utility segment, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) and Wood Mackenzie. They also forecast 37% growth for 2020 as a whole — and another 100GW from 2021 to 2025. That’s a 42% jump in installations compared to the past five years.

Most of today’s installations are new systems, but a growing amount are replacements for ones that have reached the end of their useful life or been damaged by storms. Photovoltaic (PV) technology also keeps improving, as do tax credits and other incentives. Systems designed to last 20 years sometimes are replaced after a decade with new technology that offers more power and density.

“We’re seeing those early [2000-era] systems being decommissioned now,” says Sam Vanderhoof, CEO of Recycle PV Solar, a South Lake Tahoe, Nev.-based firm that works with contractors, PV manufacturers, and others. “Twenty years is a long time for something to be out in the sun.”

And then there are the hurricanes, wildfires, and other natural events that, ironically enough, solar is supposed to rein in by reducing greenhouse gases.

“Weather-related issues account for almost 50% of failures,” Vanderhoof says.

One recent example is a 60MW solar plant in Texas that was obliterated by a tornado just eight months after going into operation. Roughly 250,000 panels had to be disposed of quickly to make room for their replacements.

“There were funds allotted to it, but it’s usually amortized over 20 to 30 years,” Vanderhoof says. “When something like that happens right away, it’s a fire drill to find out what to do with the panels and the cost of it. We’re seeing more and more of these.”

The bottom line: As the installed base grows, so does the amount of modules, inverters, batteries, and other components that have to go … somewhere — that somewhere is where challenges creep in for electrical contractors serving the residential, commercial, and utility solar markets.

Today, damaged and obsolete PV components often wind up in landfills. However, federal and state laws are steadily closing the door on that option — and at a time when recycling facilities are literally few and far between.

“It’s a ticking time bomb coming up,” Vanderhoof says. “It’s something that the solar industry is struggling with.”

Recycling also is starting to come up in customer conversations.

“It’s sporadic, but it’s something that people are starting to think about and talk about as projects get repowered and new technologies are coming,” says Joe Brotherton, vice president of renewables at San Diego-based Helix Electric.

What’s inside counts

Some PV system components are easier to recycle than others. For example, a local metal recycler will take the aluminum frames and copper wiring, while the lead acid batteries can go to a recycler that takes car batteries. Inverters sometimes can go to electronic waste companies that take computers and TVs. Panels are a different story.

“Damaged solar modules likely end up in dumpsters,” says Bob Solger, founder and managing partner of Solar Design Studio, a Platte City, Mo.-based firm serving the Midwest and West Coast. “The few that I’ve recycled, I’ve taken them to electronic recycling and made a few bucks.”

One factor is whether the contractor has already done some disassembly — a labor cost — or whether it’s providing the recycler with the whole system.

“The recyclers around here… they just view it as ‘they’ve got an aluminum frame’ and take care of the metal,” Solger says. “But the silicon and the glass, I don’t think they put much thought into how to recycle the solar module. Separating the glass from the rest of the module is pretty tough because of the way it’s sealed. Then you have the backsheets, which typically are a plastic type of material for several manufacturers. Others use some sort of aluminum or metal backsheet.”

Some electrical contractors say they’d like to see module manufacturers provide detailed information about what’s inside their products. This would enable informed decisions, such as whether a retired, undamaged system should be recycled or repurposed for a customer with a tight budget.

“From a panel manufacturer standpoint, it would be great if something came out saying what could be recycled or how it could be recycled,” says Helix’s Brotherton. “The frame can be recycled, but the technology inside? I don’t know. So, I’m either going to throw it away, or see if it works someplace else.”

Brotherton would like to see a program that clearly spells out the recycling options and monetary value for each module type: crystalline, polysilicon, thin film, and so on.

“Not knowing the potential revenues or the essential costs to collect [those] revenues is a hindrance to this growing into something,” he says. “This [wouldn’t be] the marketing ‘useful life’ pitch. This is the legitimate, science-based useful life: ‘This is good for 10 years. After 10 years, here’s what should be able to be reused, scrapped, repurposed — whatever the case may be.’”

The same system could apply to other components, such as inverters.

“Year 10, we’re replacing all these inverters,” Brotherton says. “There’s all kinds of parts and pieces in those. I’d like to hear from manufacturers what is able to be reused or recycled. Are manufacturers willing to take them back?”

Spend $25 to make $2

Manufacturer-provided information also could help the slowly emerging ecosystem of recyclers that specialize in PV. For example, Recycle PV Solar currently accepts monocrystalline and polycrystalline panels but not thin-film models.

Growing that ecosystem would help electrical contractors by increasing the chances that there is a PV recycling provider in the states where they do business. This would reduce shipping costs, which must be passed on to the customer. Today, those costs can be steep because the closest facility usually is hundreds of miles away.

“Unfortunately, the network of folks who have the programs in place — the capacity to handle the volume that I think is coming — are not in the solar hot spots [such as California],” Brotherton says.

The European solar market is worth studying for several reasons, including the European Union (EU) framework that makes it cheaper and easier for contractors and their customers to recycle. In the EU, PV manufacturers pay into a system that subsidizes recycling. Washington is among the states considering a similar program.

“Today, recycling of PV panels in Europe is common” says Bertrand Lempkowicz, head of public affairs and communications at PV CYCLE, a trade association based in Brussels, Belgium. “We’ve been recycling panels since 2007.”

A series of EU mandates also has made PV recycling a classic volume play: As the amounts increased, the costs decreased. That’s the case for a lot of businesses, but especially so for PV recycling due to the specialized equipment and processes for modules.

“Below a ton, nobody will buy it for a reasonable price,” Lempkowicz says. “If everyone in the U.S. was obliged to recycle, the cost would be less than 50 cents per panel instead of $15.”

That would help narrow the gap between costs and revenue.

“A solar module generates all of $2 in aluminum, copper, glass, lead, silicon, and silver,” says AJ Orben, vice president of We Recycle Solar, a Phoenix-based company that serves contractors, utilities, and manufacturers. “That’s after somewhere between $15 and $25 in raw processing costs. It’s a complete loss. That’s the reason why you don’t see more companies doing this.”

Europe also shows just how much of a module can be recycled.

“It’s between 80% for older recycling plants or multi-purpose units to 95% for the latest technology,” Lempkowicz says. “But there’s even a purpose for the ‘loss.’ The dust from the process [that is] captured in filters, and the residue of backsheet, will be used for energy recovery: incinerated to produce electricity.”

A $50,000 surprise

In the United States, another challenge is a thicket of federal and state regulations, including ones that determine which types of PV modules are considered hazardous waste. Some manufacturers are helping contractors with recycling programs — albeit for only their products.

“In California, thin-film modules are considered hazardous materials,” says Helix’s Brotherton. “Being able to pick up the phone and say, ‘First Solar Recycling, I have 2,000 of your modules that need to leave,’ we get a quote, they show up, and I don’t have to worry about it — that’s easy for me.”

Labor and logistics are two additional factors — and costs. It’s one thing to find a recycler. It’s another to get everything loaded onto pallets and into trucks or shipping containers. Hence the appeal of a turnkey recycling solution that covers every step after the equipment is removed.

“The thing I don’t want to manage if I can avoid it is labor,” Brotherton says. “My electricians aren’t going to stack efficiently, load efficiently, and manage logistics to get it off site. Does that mean I need a logistics team now? That’s an added cost.”

It’s important to identify all the costs and regulations before agreeing to take a customer’s system. Before joining We Recycle, Orben worked for electrical contractors and remembers one who didn’t charge a school district for taking 1,000 panels because he assumed he could get a recycler to pay for them — not so.

“We just told a guy who didn’t charge anything that he’s going to pay like $50,000 in disposal costs,” Orben says. “He hit the roof. ‘What am I supposed to do?’ They take it thinking it’s no big deal or that they can get paid.”

The $5 blue tarp solution

For electrical contractors, another challenge is passing on the cost of recycling. State mandates can help because they can be cited as the reason, especially when recycling is presented as a line item rather than rolled into the bid. Recycling or even repurposing the system can be a plus if the project is going for a LEED certification.

“Panels that still have a serviceable life and can be repurposed could count toward material reuse and help project teams lower their whole building life cycle assessment impacts,” says Brendan Owens, senior vice president at the U.S. Green Building Council. “LEED’s Building Life-Cycle Impact Reduction credit encourages adaptive reuse and optimizing the environmental performance of products and materials.

“If they are able to be recycled ― and not deemed hazardous waste ― they could be included in waste diversion calculations described as part of LEED’s Construction and Demolition credits.”

In a competitive market, some contractors flout the law to keep their costs and bids low. One reputable contractor approached Recycle PV Solar, which provided an estimate. After some back and forth, the contractor went the landfill route.

“They said: ‘Why would we pay $15 to $20 per panel to recycle? We can go to Harbor Freight, buy a blue tarp for $5, wrap the panels in it, and dump them in the landfill,’” Vanderhoof says. “That mentality is definitely there.”

But it also can come back to haunt if the government starts peeling back some of those tarps. A prime example is the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980, also known as the Superfund.

“If that dump becomes a Superfund site — which happens all the time because of aerosol cans, paint thinners, anything that the EPA considers a hazardous waste — the state and feds go through the list of anyone who has contributed waste to that site within X number of years,” Orben says. “Under CERCLA, you are considered ‘joint and several liable.’ Essentially you end up paying hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars in cleanup costs and health assessments for anyone living in that area. It’s a situation that utilities understand very, very well, which is why they’re generally willing to pay for the [recycling] service.”

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].

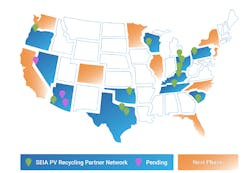

SIDEBAR 1: PV Recycling Partner Network

Launched in 2016, the Solar Energy Industries Association’s National Recycling Program features a network of partners whose services are available to any installer or PV system owner. SEIA membership isn’t required. This map shows the current and pending partner locations as of January 2020. “We aim to add 2-4 new partners yearly and for both new and existing partners to expand their collection and processing locations,” SEIA says. For more information, visit https://seia.org/initiatives/seia-national-pv-recycling-program.

SIDEBAR 2: PV Recycling Preparation Pointers

The Solar Energy Industries Association has a lengthy checklist that contractors can use to prepare PV equipment for recycling. Some examples include:

- Collect manufacturer’s name and serial numbers of each product to be recycled.

- Check that the recycler has the appropriate R2 or e-Stewards accreditation in addition to complying with EPA permitting requirements.

- Ensure that you will receive a Certificate of Destruction/Recycling for the products sent. Request that this be sent with the invoice (or check if credit is to be owed back to your business for the recycled product).

- Provide Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) or similar information on the type of PV modules (i.e. mono/polycrystalline, thin-film etc.)

- If using pallets, it is recommended that you stack the pallets between 28 and 35 modules high to make them economical to ship and to avoid any further damage to the panels.

- The average truckload of PV modules, when palletized as suggested, can hold between 12 and 13 pallets and weigh on average between 18K lb and 20K lb.

Download the full checklist at https://www.seia.org/sites/default/files/SEIA-PV-Recycling-Checklist.pdf.

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].