Twenty years ago, solar cost more than $15 per watt to install, according to the research firm Wood Mackenzie. Now it’s under a buck and still heading south.

There’s promise and peril in that trend. On the plus side, declining prices make solar attractive to more customers — from homeowners to electric utilities. But a booming market also attracts hordes of vendor newcomers looking for a piece of the action. More competition helps drive down prices, yet heavy competition also makes it tough for vendors — particularly startups and other smaller ones — to price their products high enough to fund enough R&D for market-differentiating performance and features. It also leaves less money to cover warranty claims.

For people like Joe Brotherton, those market conditions mean lots of legwork to figure out which vendors have the staying power to support their products years down the road.

“I walked in this morning to two voicemails from companies I’d never heard of,” says Brotherton, vice president of renewables at San Diego-based Helix Electric. “One said they have 50MW to put in place this year. Another said they’ve already put in 350MW and are looking to do another 100MW this year — all in the commercial space.

“Never heard of them. Went to their websites and never heard of any of the individuals [running the company]. Who are we hooking our trailers to?”

Failure is an option?

When a vendor exits the U.S. market, goes bankrupt, or struggles to honor its warranties, it can drag down the brand reputations and bottom lines of the contractors it works with. That risk isn’t unique to solar, of course, but the odds are higher than in a lot of other industries.

“There are so many newer companies, especially from Asia, that were startups that failed,” says Sam Vanderhoof, CEO of South Lake Tahoe, Nev.-based Recycle PV Solar. “We’re not talking about a few — more than a thousand.”

Recycle PV Solar helps contractors, manufacturers, and others safely dispose of equipment that’s damaged, obsolete, or orphaned. That means every day, Vanderhoof sees contractors and end-users struggle with vendor exits.

“It’s not a new phenomenon,” he says. “It’s a major problem right now.”

Just ask J. Scott Christianson. Right after installing a 24-panel system on his home in Columbia, Mo., some of the microinverters stopped showing up in the monitoring system. Thus began a six-year-plus saga that he documented on Reddit.

“The inverters have a 20-year warranty — one of the reasons we purchased them,” he wrote. The manufacturer sent him new ones, but he had to install them himself.

“I now have another inverter that will not talk to the system,” he wrote, adding that the manufacturer seems to have left the U.S. market. “I have had no luck getting in touch with them, and the distributor has only offered to sell me a different brand — and has had no better luck getting in contact with [the manufacturer].”

If misery loves company, then Reddit solar threads offer plenty of both. One response to Christianson came from a person who works in the commercial and industrial space, where another brand of inverters “literally vibrated themselves apart” on a project.

“The owner sued them, and they gave them money to rewire the whole plant since they could not service their warranty,” that person wrote. “For anyone that reads this, warranty is only as good as the company that is willing or capable to service it.”

The devil is in the details

Even when a vendor is willing and capable, it’s still important to scrutinize the warranty’s fine print.

“Warranties are crap,” Brotherton says. “Every single one has holes in it. Our industry I feel is one that you can’t say: ‘It’s only this type of product’ or ‘It’s only the product that comes from this country.’

“A particular inverter manufacturer says if it’s within, I think, 13 miles of the ocean, we need to do something special for it. No one is going to pay for a stainless-steel enclosure for an inverter that’s going on a shade structure at an elementary school.”

When customers want a particular vendor, Helix educates them about the warranty requirements.

“We say, ‘Just to let you know before we get started, here are parts of this project that may have an effect on the warranty,’” Brotherton says.

One challenge is that contractors and their customers see only the warranty itself rather than its financial foundation. For example, one vendor’s marketing highlighted how its 25-year warranty was backed by Lloyd’s of London.

“Come to find out, they paid their premium monthly,” Vanderhoof says. “The whole thing collapsed.”

For contractors, another factor is whether they’ll be reimbursed — fairly or at all — when they help fulfill a vendor’s warranty.

“Most companies have warranties that say if you have problems with your solar panel, we’ll replace it for free,” says Barry Cinnamon, CEO of Campbell, Calif.-based Cinnamon Energy Systems. “Great! A solar panel sells for $200. It costs me $200 to send a crew out to remove it. It costs me $200 to send someone back to put it on. That can’t be done in one trip because they require them to evaluate the panel. You have to ship it back to them first, and it costs $200 to ship the panel.”

That works out to $600 to replace a $200 solar panel. Will the contractor get reimbursed for that $600?

“I hate to say it, but when that happens with these companies that I don’t trust on the warranty, I just replace the panel myself,” Cinnamon says. “It’s not worth the brain damage of trying to get the warranty met.”

Bigger is better

Even so, warranties remain a compelling selling point, especially in the residential market. Hence the vendor one-upmanship: first five years, then 10, then 25.

“It’s all a marketing thing,” Vanderhoof says. “I don’t think consumers grasp that.”

Some vendors have gone out of business because they couldn’t cover their warranties. One school of thought says that vendors big enough to be household names also have the financial scale and business-line diversity to back their warranties.

“Companies like Kyocera, BP, Hyundai, and Sharp have enough stability with their other businesses that it doesn’t tank their solar business if they have a diode failure or something,” Vanderhoof says.

Another school of thought says that household names don’t want problems in their solar business sullying their overall brand, so they’ll bend over backward to back their warranties, particularly in the residential market.

“The big companies — Panasonic, LG, the ones that really care about their consumer warranty — they’ll bend over backward,” Cinnamon says. “Kyocera comes to mind. They’re one of the best. Sharp also is very good.”

But others question whether big, diversified companies are an inherently safer bet for contractors and customers alike.

“I don’t really take that into account only because these big companies can just flat out shut something down and not support it at all overnight,” Brotherton says. “They can deal with the complaints.”

Another factor is the vendor’s location. If it exits the U.S. market, then pursuing a claim could require hiring a law firm with international expertise. That’s often cost-prohibitive.

“You can’t go after them,” Cinnamon says. “So, I think the biggest hazard for electrical contractors — especially with batteries — is going with a battery or a system from a company that doesn’t already have a well-known U.S. brand.”

Some types of customers have more flexibility when it comes to accommodating a warranty’s terms. For example, some warranties will provide additional modules to augment the existing ones when they experience a certain level of power degradation. Utility and commercial customers are more likely to have the roof space to accommodate the additional modules than consumers are. This also is an example of how warranties are continually evolving.

“The warranties are really different than they were 10 years ago,” Vanderhoof says. “They’re now sometimes for quality of workmanship and only for a short period. Then there’s power degradation over time. That can fade out like a car tire warranty, where it’s not worth as much toward the end.”

Batteries are another problem area.

“We all know that batteries don’t last that long,” Cinnamon says. “There’s a lot of new companies, a lot of overseas companies, a lot of new technologies. They all say they have a 10-year warranty on their batteries; otherwise, they can’t sell them. Some of those aren’t going to work.”

Insurance and O&M firms to the rescue

It’s inevitable that more vendors will go out of business, so what can regulators and the industry do to protect contractors and customers? One possibility is an escrow fund to support orphaned systems. California considered that over a decade ago, but it never went anywhere.

“The industry just couldn’t afford to pay that,” Vanderhoof says. “As an industry, we’ve got ourselves in a dilemma. There’s no real clear way of dealing with this. Some kind of insurance policy probably is the best bet.”

One example is GCube Insurance Services, which says it’s underwritten more than 20GW worth of systems globally since 2005.

“Several solar manufacturers offer warranties as a way to give peace of mind to contractors and customers that there will be someone backing the product even if the manufacturer is no longer in operation,” says Evelyn Butler, Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) vice president of technical services. “Like many other products, warranties are backed by third-party insurers or similar organizations.

“Some businesses have emerged to provide operations and maintenance (O&M) services and production guarantees if the system does not routinely perform as expected. It may not guarantee that the equipment manufacturer will be around, but it does provide assurances to the customer that there is a process to manage product repair and placement.”

Demand for O&M services is reflected in how those companies are scaling up.

“In our latest analysis, published in July last year, we identified 13 major transactions with seven of them concentrated in the U.S. — most of them M&As involving American companies,” says Leila Garcia da Fonseca, Wood Mackenzie principal analyst, energy transition. “These service providers are usually capable of handling all O&M tasks, including repairs and replacements of orphaned components from suppliers that are out of the market. While there are several Asian components manufacturing companies supplying the global solar industry, service providers tend to be more local.”

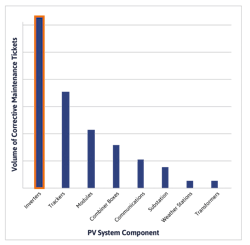

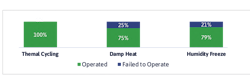

Another resource is PV Evolution Labs (PVEL), which provides reliability and performance testing for modules and inverters. Its Scorecards are like Consumer Reports: a crash course about a product type, purchasing tips, and a rundown of how each vendor’s product fared in tests. See Fig. 1 for an overview of which PV system components generate the most maintenance tickets. For example, its Inverter Scorecard includes thermal cycling and humidity freeze tests, where 21% to 25% failed to operate as intended (Fig. 2).

Recycle PV Solar gets a lot of calls from people trying to sell their homes, but an inspection reveals inverter problems, and they find out that their installer no longer is in business. This points to O&M opportunities in the residential market, too.

“Nobody wants to touch an older system that they didn’t install themselves,” Vanderhoof says. “In 2020, more than a gigawatt was decommissioned in the U.S. Why? Could they still be used? So, O&M companies are starting to pop up.”

Whether the end-user is an electric utility or a homeowner, O&M companies can be a source of parts that are tough to find.

“There are distributors that sell replacement parts, as well as third-party O&M service providers that might be able to find suitable replacement parts,” Butler says. “Purchasing refurbished equipment might also be an option, but it depends on what was fixed and the status of the product safety certification post-refurbishment.

“If the PV system is leased, the third-party owner is responsible for post-installation service, product replacement, and repair. If the system is owned outright, we highly recommend contracting with an O&M service provider that can assist with performance monitoring, product replacement, and repair.”

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].