Surprise is part of the enforcement toolbox that inspectors with the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) employ, but it’s probably not an emotion they share with employers as they assess job sites and uncover violations that could compromise worker safety. Rather, their reaction may be closer to one of “here we go again.” That’s because for several years running, inspectors — who enter workplaces under varied pretenses, including intentionally unannounced visits — have been finding mostly the same collection of violations of federal workplace safety rules. Going back at least six years, OSHA’s official and publicized tally of the top 10 most frequently cited violations for the prior fiscal year has remained close to static in composition, though violation numbers have fluctuated, and rankings have shown some play.

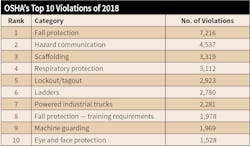

OSHA’s FY 2018 list, unveiled for emphasis once again at the well-attended 2018 National Safety Council Congress & Expo in October, fits the mold. Except for one category that leapfrogged another into the top 10, the list (see Table above and the Photo Gallery on EC&M’s website at https://bit.ly/2FsI3bp) is nearly identical to last year’s and closely resembles previous ones stretching back to 2013. A notable change: For the first time in six years, neither violations related to OSHA rules on the proper installation and use of electrical conductors and equipment nor those relating to electrical wiring methods and components made the top 10 list.

But violations broadly related to protecting workers from falls, one of the biggest sources of workplace injuries and an emerging OSHA priority, were clustered in the 2018 top 10 for the sixth straight year. Four separate categories, each linked to a separate and specific OSHA rule, made repeat appearances on the list: fall protection; fall protection training; scaffolding; and ladders. Also, violations linked to rules crafted to prevent injuries from encounters with machinery and equipment formed another grouping that’s long been on the list: lockout/tagout; machine guarding; and powered industrial trucks. The 2018 list was rounded out by two violation categories addressing worker contact with harmful substances or environmental hazards: hazard communication and respiratory protection, both of which have made regular top 10 appearances; and one making its debut: personal protective and lifesaving equipment — eye and face protection.

Consequential Violations

The list’s consistency may have several sources, and they’re likely linked. Most violations have a proven connection to comparatively high injury or fatality rates; therefore, they constitute a collection that can lead to the worst outcomes. Inspectors, in turn, may have their eyes peeled for them. Additionally, they also may be so routine that they’re hiding in plain sight and require little unearthing on the part of inspectors. And, when they’re discovered (sometimes during the investigation of a related injury), OSHA may have little reluctance to pull out the stick.

Yet while the same violations keep making the most-cited listed, the number of findings, by one measure, has barely budged over the last half-decade. Violations in eight categories that are perennially in the top 10 were little changed from 2014 to 2018, falling imperceptibly from 28,570 to 28,137. That could be read many ways. Scant progress has been made in getting employers to comply with these OSHA rules, OSHA is staying vigilant on areas of key concern, or at least violation numbers haven’t spiked.

But what can be inferred with near certainty about OSHA’s list is that many workplaces and job sites remain plagued by recurrent safety lapses that can bear potentially tragic consequences, and that OSHA isn’t taking its eye off the ball. The agency knows what causes injuries and continues to hone in on violations of key workplace rules written to help prevent their occurrence. But now, after several years of OSHA pointedly highlighting areas of top concern, attention, and regulatory action, the question remains: Why do these violations persist, and what can be done to bring the numbers down?

Donald Martin, senior vice president of consulting for the organizational safety and reliability group of DEKRA Insight, Oxnard, Calif., says one takeaway from the consistency of the OSHA list is that agency resources have stalled.

“When you have a relatively static number of inspectors, and the objective is to inspect about the same number of workplaces each year, there’s reason to expect they’d find about the same number year to year,” he says, adding that even going full tilt OSHA could only inspect less than 5% of workplaces annually.

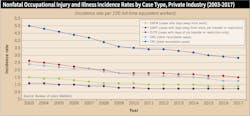

The violation categories remain basically the same, he says, because they’re commonplace, and evidence is strong that they’re strongly linked to bad outcomes. Even though there’s data showing reportable “other-than-serious” injuries have steadily fallen to a recent record 2.8 per 100,000 workers (Fig. 1), he says, that doesn’t account for more serious injuries, and the fatal injury rate has stayed stuck at around 3.5 for the last several years.

Focusing on “Serious”

Evidence that the top 10 violations list is highly correlated to fatalities and serious injuries lies in another OSHA list that Martin says warrants more attention. That’s its top 10 list of “serious” violations — those OSHA say carried a high probability of death or serious physical harm and that either were (or should have been) recognized as such by the employer. Again, in 2018, the serious-violation list is a majority subset of the top 10 most cited list, meaning the lion’s share of violations in each category were potentially highly consequential. For example, 81% of 2,700 lockout/tagout and fall protection violations were serious, while on the low end 66% of respiratory protection violations and 67% of powered industrial truck violations met the definition. Violations deemed serious, Martin says, usually have their roots in the absence or insufficiency of critical controls, defined as procedures and practices employers should have in place to protect lives.

“What OSHA is seeing is a proxy for what everyone would see if they went into the field,” he says. “They’re saying with this list that they keep finding breakdowns in these controls.”

They’re occurring, he theorizes, because too many employers misinterpret data showing workplace injuries are declining, and think safety is improving the longer they go without serious injuries. But over time, vigilance in protecting workers can wane, and conditions can grow more dangerous.

“A lot of safety managers are spending less time in the field verifying that critical controls are in place and functioning,” he says. “They can be deluded into thinking they have all fatal and serious injury exposures under control. What’s needed is a constant sense of vulnerability (Fig. 2).”

The OSHA rules being violated are detailed prescriptions for gaining that control, and they’re being skirted or ignored because in many cases cited companies lack an effective organizational safety mindset, says Mike Behm, professor of occupational safety at East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C. The prevailing workplace safety culture, he says, is still too quick to place ultimate blame for injuries on careless, distracted, or inattentive workers.

“Too often we’re focused on what a worker who falls and dies did or didn’t do, when we should be looking at what supervisors, managers, facility owners, or engineers did to anticipate the risk and prevent that outcome,” he says. “We need to move to thinking about workplace safety upstream of where the work is actually happening. We’ve been tactical about safety when we need to more strategic.”

But tactics matter, says another safety professional, Jim Stanley, president of FDR Safety, Franklin, Tenn. Workers do bear a lot of responsibility for injuries, and that dilutes some of the significance of the OSHA top violations list, he says. Layers of controls that accord with OSHA rules can’t always overcome workers who are lax about personal safety. Equally or more important is behavioral change, which employers can help foster.

“We can train until we’re blue in the face, but what usually produces injuries is ‘you,’” he says. “Employers do have a responsibility to do the brick and mortar of safety and enforce rules and to be held accountable, but the rubber meets the road with workers.”

It’s important for employers to be aware of the OSHA list, Stanley says, but it’s ultimately a tally of easy-to-spot violations that present only part of the story of how and why workplace injuries occur: “It’s low-hanging fruit.”

But the list has educational and remedial value, OSHA says. It serves as a reminder of the most potent dangers that can exist in workplaces, the agency says, ones that can be reduced with greater awareness and the application of well-tested risk-mitigating programs, procedures, and training.

To make it more useful, the deputy director of OSHA’s Directorate of Enforcement Programs, Patrick Kapust, told the National Safety Council’s official publication that employers should try to determine which violations have the most relevance to their industries and then assess their workplaces for risks and compliance with applicable OSHA standards. He advises consulting the OSHA frequently cited violations database that breaks down citations by industry sector using federal NAICS codes.

Consulting that, one finds that industry sectors most likely to employ electrical workers in various capacities, along with others — electrical contracting service businesses, construction, manufacturing/industrial, utilities — have vulnerabilities in most of the categories on OSHA’s leading violations list. Numbers and rankings varied, but workplaces in those sectors were cited by OSHA for everything from fall-related hazards, respiratory protection, and hazard communication to lockout/tagout, powered industrial trucks, and eye/face protection. While exposures are higher for them in some areas than others, electrical workers can encounter an array of hazards while performing their duties.

Falls a Top Concern

One that’s clearly a thorny problem for industries, businesses, and workers of all types is falls, particularly those from heights (Fig. 3). Every year since 2014, violations of OSHA fall protection rules have topped the agency’s list, and most have been classified as serious, easily exceeding the runner-up. Of the 7,216 in 2018, almost 80% were serious. Plus, 134 were termed “willful,” and 1,021 were repeat violations. Construction settings, where the relevant OSHA rules mostly come into play, were responsible for about 6,700 of the overall total. And “specialty trade contractors” were by far the most cited.

While separate rules categories distinct from fall protection, those relating specifically to fall protection training, ladders, and scaffolds — all of course “fall-linked” — are also consistent trouble spots that OSHA targets. It found 3,319 violations of scaffolding rules, which landed third on the 2018 list; 2,780 ladder rules violations, which were sixth-ranked; and 1,978 violations of rules pertaining to training workers on fall protection, which were eighth on the list. Specialty trade contractors racked up a fair share of violations in each, while scaffolding was more of a problem for manufacturing companies.

OSHA is right to have fall/working-at-height violations in its crosshairs, Martin says, because Bureau of Labor Statistics data show falls caused 17% of work-related fatalities last year.

“Falls have increased, and that fatality number is up 2% from 2017,” he says. “That puts a real laser dot on the issue.”

Rules addressing falls merit special attention, Martin says, because employers often don’t fully evaluate the risks workers can face. Not understanding that falls from 10 feet or less cause a quarter of all fatal falls — and that falls from 6 feet or less cause 12% — many don’t fully comply with rules designed to prevent them. OSHA rules generally cover the need for guardrails, safety nets and fall-arrest systems; secured, regularly inspected and properly positioned ladders; properly built and guarded scaffolding; and programs for training workers to understand fall hazards and procedures for minimizing them.

Falls are highly preventable with proper work planning, Behm says, but employers struggle to address every scenario involving work at heights. Some have recognized that and tried to craft end runs around the problem, he says; he knows of one construction company that now tries to structure work so ladder use is a rarity.

Equipment Encounters

Where falls present a big risk in construction settings, traumatic encounters with “live” equipment are an ever-present risk in manufacturing environments. Many risks to operations and maintenance workers, electrical and otherwise, can be reduced by establishing and following lockout/tagout (LOTO) procedures to block contact with hazardous energy; preventing incidental contact with operating machinery and equipment using guard mechanisms; and ensuring powered truck equipment is properly and safely designed, maintained, and operated.

But as with falls, these are areas many employers seemingly struggle to address. Hazardous energy control rules violations in 2018 totaled 2,923; there were 1,969 documented violations of rules on machine guarding; and OSHA found 2,281 violations of safety rules governing powered industrial trucks.

LOTO rules compliance is a stubborn problem because procedures can be complex and must be religiously followed, says Richard Current, P.E., a research safety engineer with the federal government’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which has been developing tutorials through its National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) manufacturing sector council to help businesses understand and implement LOTO.

“The most violations have to do with either not having a program in place or not performing procedures,” he says. “For a lot of contractors and companies, lockout/tagout is complicated, but if it’s not planned for you, they come up with things on the fly which may not be the safest.”

LOTO rules violations documented by OSHA last year encompassed failure to develop, document, and utilize procedures; conduct annual procedure inspections; and to thoroughly train employees in implementation.

Shielding machinery so that workers can’t come into contact with its activated and possibly exposed parts, leading to amputations and other trauma, presents similar challenges for employers. While proper and effective guarding is key, most of OSHA’s citations related to failure to deploy guarding to protect operators or others from hazards posed by rotating or other moving parts, flying materials and sparks.

That’s predictable because effective machine guarding can be a challenge, especially with older equipment, says David Parker, senior physician researcher with HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, who is on the NORA manufacturing sector council and has studied machine guarding issues.

“It can be complex,” he says, because so many exposure elements must be addressed, and because “owners of older equipment may be reluctant to invest in guarding it.” More modern machinery comes with guarding incorporated, he says, suggesting compliance might increase over time as replacement cycles advance.

Machinery, the energy that powers it, and heights pose some of the deadliest hazards in workplaces, but OSHA is vigilant on others. It found 4,537 violations of rules pertaining to detailed, clear communication to workers of hazards of all chemicals present in the workplace in 2018; 3,112 incidents where proper respiratory protection of workers was or could have been jeopardized; and 1,528 cases where workers could not or did not effectively protect their eyes and face from a host of hazards.

Those violations round out the top 10 list, but it bears noting that OSHA regularly logs scores of others. Just below top 10 were violations of rules on electrical wiring methods, components and equipment, numbering 1,342, and those covering “general electrical,” coming in at 1,189, indicating they’re far from being tamed. Beyond that, numerous other rules exist to protect workers, and employers are subject to enforcement action if they’re violated.

OSHA, however, will likely continue to focus on violations that bear the most consequences, and it’s a good bet the 2019 top 10 list will be little changed. Violations in those categories are common to many industry sectors, but there’s little doubt that OHSA will continue to prioritize them for enforcement and encourage employers to ratchet up vigilance.

“In most cases, these violations are for safety issues that can be addressed if employers assess the hazards, make corrections, and train their employees,” says an OHSA spokesperson.

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].