Every year through 2031, the electrical industry will have an average of 80,000 job openings, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. That’s roughly 11% of all positions. Those numbers mean that for the foreseeable future, any job opening will be tough to fill. But some will be tougher than others.

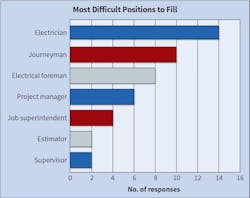

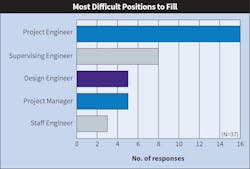

Each year, EC&M surveys the largest electrical contractors and electrical design firms about a variety of topics, including “most difficult positions to fill.” In the September 2022 Top 50 Electrical Contractors survey, “electrician” was deemed the toughest, followed by “journeyman,” as shown in Fig. 1. And in the June 2022 Top 40 Electrical Design Firms survey, “project engineer” ranked first, followed by “supervising engineer,” as shown in Fig. 2.There’s also an ironic conundrum: Engineers are in such short supply that they can practically name their price, but many don’t put themselves in a position to exert that power.

“Engineers at these levels are working,” Burnside says. “They don't typically apply to open positions posted on job sites or company websites unless they have a compelling reason. That can be job flexibility, salary, work environment, or several other issues. I believe they get caught up in day-to-day tasks and may be too busy or exhausted to think about a change. A large part of my job is to reach out to these passive candidates and start the conversation of ‘what if?’”

Menasha, Wis.-based Faith Technologies Incorporated (FTI), an electrical contracting and engineering firm that is listed on both EC&M's Top 50 Electrical Contractors and Top 40 Electrical Design Firms lists for 2022, is doing similar outreach.

“Post COVID, it has been an interesting couple of years,” says Jami Garrity, director of talent acquisition. “We did have a surplus of individuals applying, and now we're on the opposite side where we are actively reaching out to what we call ‘passive’ candidates and saying: ‘Here’s why FTI is better than the individuals that you're working for now. We're a growing company. We have a record amount of backlog for 2023.’ We have individuals that actually come back because they recognize that our safety is top-notch.”

Specializing in highly complex projects also can limit a firm’s pool of potential candidates.

“Our projects consist of larger and more complex designs,” Burnside says. “Finding candidates with the knowledge and experience of these projects proves more difficult to source. Ideally, our mid to senior engineers should be licensed in the state they practice.

“Depending on workload, we hire entry-level design engineers (zero to two years) to senior-level project managers (minimum seven to 10 years). We look for mid- to senior-level candidates with experience in larger, more complex projects, including health-care facilities, upper and lower educational facilities, technology and laboratory facilities, and larger federal projects, such as airports and seaports.”

Leaders needed

Finding experienced people who also are willing and able to take on leadership and mentorship roles is another challenge across the board.

“We definitely see the journeyman role being the most challenging position to fill,” Garrity says. “Fortunately, we have a lot of opportunities to come in as what we call a ‘ground-up growth hire.’ We'll bring individuals in with zero electrical experience and have them go through a variety of courses, including our fully paid apprenticeship program where they're going to get those skills to be able to take the journeyman test. A lot of the time is spent on site where they're working alongside different crews and being able to learn from individuals who have been in the trade for quite some time.”

San Jose, Calif.-based Rosendin Electric faces a similar struggle.

“The less experienced and those entering the trade are becoming more available,” says Troy Vandine, workforce development trainer at Rosendin’s Charlotte, N.C. office. “It's the field leadership to be able to direct those less experienced people that we are really struggling to find.”

Rosendin is No. 4 in EC&M’s 2022 Top 50 Electrical Contractors listing and a national player, so it can leverage that scale to move leadership to where it’s needed — at least temporarily.

“Guys that are working with Rosendin around the country are able to come in and help provide some of the leadership,” says Bobby Emery, the firm’s workforce development coordinator for central Tennessee.

Another challenge is finding employees who have experiences — as in plural.

“A lot of the journeymen coming to work for us have always worked for contractors that kept them more task-oriented instead of well-rounded as far as their training,” Emery says. “We're struggling with that. You'll have a guy who comes in that's really good on conduit or wall rough-in, but he doesn't know how to hook up a transformer or make terminations.”

A wide range of experiences can help journeymen take on more of a leadership role.

“When you're out in the field, journeymen wiremen are leaders in themselves,” Emery says. “They're able to take direction from their foreman and direct two or three workers that are working with them.”

Sharing is caring

A well-rounded journeyman also can be a great mentor, but unfortunately, that’s not always the case. Therein lies another ironic problem for employers: Although everyone in the electrical industry bemoans the chronic shortage of people, some still fear being out of a job.

“In our region, a lot of journeymen — I would say close to 40% — feel if they pass that knowledge down, it may limit their ability to keep their job or to have a job in the future,” Emery says.

His colleague Vandine adds: “With me and Bobby, when we got into the trade, there was somebody that took us under their wing, showed us the ropes, took the time to tell us when we were wrong, and praised us when we were right. That seems like a lost art.”

Some firms are addressing the labor shortage by creating their own apprenticeship programs. Obviously, that strategy requires veteran employees willing to share their expertise.

“Because we have our in-house apprenticeship program, we also have in-house training,” says FTI’s Garrity. “They're called ‘technical trainers.’ We have quite a few of them across the board because they are the individuals who are truly passionate about the trades and want to pass that knowledge along.

“We have individuals on staff that are so good with the Code that all they do is teach the Code to individuals who maybe are struggling. They can have one-on-one sessions with those individuals. They can do online training or in-person training.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests that younger employees who have begun moving up the ranks are more inclined to share what they’ve learned with those just starting out.

“I sat in a foremen meeting several weeks ago, and these young foremen were up there saying, ‘Our most precious resource in our company is our apprentices,’” says Al Paxton, chief people officer at Lakewood, Colo.-based Encore Electric. “When I heard that I was like: ‘Oh my gosh! We're probably in a pretty good place right now as long as we can continue to promote that way of thinking from our leaders.’”

Those kinds of people skills can go a long way toward keeping newcomers at a company — or even in the profession.

“If you have some adjustments to make or you have something you need them to work on, you pull them to the side so they don't feel that they're singled out,” says Rosendin’s Vandine. “But you praise in public.”

Simply stopping to talk with employees can help boost morale and retention, especially in large firms.

“We had a gentleman working here in the prefab shop,” Emery says. “I was walking through one morning, and I stopped and talked to him for 5 minutes. Just asked him how his day was going and how his family was doing and told him he was doing a great job. Then I walked on to the office.

“At the end of the day, he looked me up and said: ‘I've been doing this for several years and never had anybody take time to thank me for the job that I was doing. I just want you to know that I appreciate it.’”

How to keep who you have

Ample career options also can be key for attracting and retaining talent. In the case of people who are new to the profession, that strategy requires mentors to educate them about all the opportunities they’re unaware of.

It's equally important to show experienced employees that they have plenty of options, too.

“Foreman and superintendents all want to know what their career path looks like,” Paxton says. “It's a leadership responsibility to help both people see that it's not just a linear path. There's a lot of ways that the dots could connect.”

Some career paths are a tougher sell.

“There's a stigma with service I'm still trying to figure out,” Paxton says. “There are guys who just want to get out there and build stuff. Service is good work; it pays really well, and you’re kind of your own boss.

“We pay a premium for service techs because they've got to give us that great customer experience. They interface directly with our customers. It's more challenging to get those people in the door because we have pretty high expectations.”

Show me the money

In theory, the bigger an electrical contractor is, the more money it has to snap up talent. But the reality is different, especially when it comes to people who have completed their apprenticeship programs and are now ready to test. That’s because solid new hires can have a much bigger impact on a company with 50 electricians than a firm with 1,000.

“Smaller firms will throw a big premium at a really good, ready-to-test apprentice,” Paxton says. “The people that they want to cherry-pick — that's where it gets super competitive.”

Most apprentices also are starting out in life.

“Dollars will sway a young person, especially a young person that's got a family,” Paxton says.

Higher pay also can be attractive if it means they can provide for their family without putting in 60- or 70-hour weeks.

“Who's the most vulnerable employee?” Paxton says. “One of our senior executives said, ‘Is it the lowest paid person in the company?’ I think it’s probably the hourly employee that has the highest responsibility load: a mortgage, kids. They’re not really making all that much money, and the economy is crazy. I think that makes people more vulnerable, and they'll be easily swayed by a dollar or two.”

People with a lot of familial responsibilities also often want to know that their employer is capable of taking care of them when a sector or the entire economy starts to slow. This concern can give an edge to contractor and design firms that work in a variety of sectors — from traditional ones to emerging ones such as renewables and EVs.

“If we have a recession, maybe that electrician can learn something new and put up a solar panel instead of [working in] the traditional industrial space,” says FTI’s Garrity. “We have a lot of different manufacturing environments if someone doesn’t want to work out in the field anymore or in office settings. We've got virtual design programs, estimating programs, and operational leads that are needed.”

Tim Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].