Amidst tumbling fossil fuel prices, the flowering of new oil and gas extraction technologies, and the snail’s pace adoption of alternative energy, it can be tempting to declare interest in energy conservation officially in hibernation. But even at a time of sub-$2 gasoline, many heavy users and dominant suppliers of energy know that any vacation from concerns about global energy consumption trends is temporary, at best.

The alarming concept of “peak oil” may be tarnished, yet it’s a near certainty that the long-term trajectory for supplies of traditional sources of energy is down, while that for its costs — broadly measured — is up. And so even as debates about energy supply and demand, costs, and its environmental impact continue, interest in methods of slashing energy usage and costs persists. One prime indicator of that is the robust performance of the broad energy services sector.

By some measures, business is booming for suppliers of energy savings performance contracting (ESPC) services — those operating as energy services companies or ESCOs. Demand for their services, which typically revolve around efficiency upgrades to an extensive range of facility infrastructure components that use or impact energy consumption, and are paid for partially with the savings, may have actually outpaced the GDP growth rate in the sluggish period of 2009-2011, and has continued to strengthen. Now, there are predictions that the industry could conceivably double within five years as more powerful incentives, enticements, and mandates come into play; new technologies emerge; and more creative and comprehensive project design and delivery methods are deployed.

Possible double-digit growth

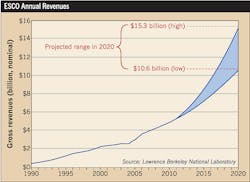

A lot would have to go right for that forecast to pan out — financing, spiking energy costs, and the opening of new markets — but industry watchers are optimistic. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), along with the domestic industry’s trade association, the National Association of Energy Service Companies (NAESCO), sees a path for ESCO annual revenues to climb from the $5.3 billion recorded in 2011 to between $10.6 billion and $15.3 billion by 2020 (see the Figure below).

“Our best guess is that industry revenues will be around $7 billion in 2015, and we’re projecting pretty significant growth over the remainder of the decade,” says Peter Larsen, an economist with LBNL’s Energy Analysis and Environmental Impacts division that tracks some 4,000 ESCO projects.

Should those targets be achieved, the benefits will ripple out well beyond ESCOs proper. Operating generally as broad solution providers, most ESCOs are structured to bring together a mix of specialized subcontractors and service/equipment suppliers to bundle energy-efficiency upgrades.

Among them, electrical contractors, systems designers, and engineers have evolved to become key players. Those specializing in areas such as lighting, on-site generation, or renewable energy systems, for instance, or with experience in markets ESCOs increasingly covet, such as commercial and industrial, will be positioned to benefit.

ESCOs are leaving few stones unturned in their quest to help clients consume less energy. In addition to lighting, one of the most commonly upgraded components in ESCO work, other fixes are drawing interest. Projects addressing direct power usage reduction and optimization can include on-site power generation systems, supplementary or primary renewable power capabilities, water pumps, variable-speed drive systems, wiring upgrades, and control and energy management systems.

“In the early days the ESCOs focused predominantly on lighting, which was the early 1990s,” Larsen says. “Now they’re focusing on 15 to 20 different measures, including HVAC, water, and on-site generation, and they’re installing solar panels. They’re doing all this stuff, and almost every one of these measures may require an electrical subcontractor to perform the work because some of this is very specialized.”

Expanding scope

ESCO projects increasingly incorporate a broader range of upgrades and improvements that can be funded with energy savings, some of which themselves may only be tangentially related to energy consumption. Roof replacement, asbestos removal, new chillers and water heaters, and a host of other improvements often accompany more commonplace energy efficiency upgrades, and require expertise that electrical contractors lack.

In delivering solutions, ESCOs will look to bring on the expertise that’s needed, and they’ll divvy it up among specialists or try to find highly versatile partners.

“Because of the shorter paybacks required, there’s a lot of potential to have a comprehensive program that’s related to all the energy consuming equipment,” says Adams. “I think that’s why there are maybe more mechanical contractors getting into the ESCO subcontracting business than there are electrical contractors, many of whom still almost exclusively focus on lighting. ESCOs need to have people with expertise in not only lighting, but also windows, doors, roofs, motor control centers, temperature control systems, and solar.”

To position themselves for new or additional work as subcontractors in the evolving ESCO space, electrical contractors will likely have to develop both broader expertise and closer relationships with ESCOs. In addition to becoming more familiar with emerging electrical technologies that address power usage, extending well beyond LED lighting, they’ll also need to become more comfortable with the prospect of extended project responsibilities and closer partnerships.

ESCOs typically develop a stable of “go-to” subcontractors who may also have to commit to provide ongoing services for ESCO projects. Larsen says more projects are being structured with operations and maintenance add-ons that require ESCOs and their subs to stay involved beyond the completion date.

“When an ESCO signs a big contract with a customer, they’ll often offer O&M adder contracts in which the customer agrees to pay a certain amount for service beyond the original install,” he says. “That’s a big difference in the ESCO model, where you have complex systems, and it’s difficult to just leave after it’s installed.”

But it’s the energy usage and cost reduction opportunities that will ultimately drive industry growth, and industry watchers believe there’s no shortage of prospects. A rapidly aging, energy-gulping infrastructure is ripe for the unique proposition that ESCOs bring to the table: the opportunity to invest in energy efficiency and leverage the resulting lower utility bills to speed payback time and/or plow the savings back into a broad range of critical facility improvements and deferred maintenance that can otherwise be difficult to fund.

ESCOs have made a significant dent in that market in the last quarter-decade, but the unrealized opportunity appears substantial. In a September 2013 study, LBNL put the remaining ESCO market potential in the United States at between $71 billion and $133 billion.

That sounds plausible to Jim Adams, a former ESCO owner who now provides consulting services to the industry as president and CEO of Golden Energy Services, Newburgh, Ind. He cites the combination of rising energy costs, mounting pressure to use less energy, and a relentlessly ticking clock as reasons to be optimistic about ESCO prospects.

“Half the buildings in the U.S. are over 30 years old, and 80% are more than 20 years old,” he says. “There’s a lot of old technology and worn-out systems in facilities, and owners of many of them don’t have the capital to replace it. Using the financing and performance contracting that ESCOs offer can provide the capital to replace the infrastructure with systems that reduce long-term operating costs. We have these issues all over the country.”

Private market opportunities

Much of that energy-guzzling infrastructure, though, is in private hands. That stark reality complicates efforts to get a true fix on how much of the sheer market potential will translate to bookable business.

Unlike the broadly defined public sphere, which due to its structure and the growth of efficiency mandates remains a dominant and steady source of business for ESCOs, the private sector has been under far less pressure to boost efficiency. Demanding quicker paybacks on any balance-sheet investment in higher efficiency, private building owners scrutinize such projects more carefully and regularly conclude that they’re unwarranted or not economically feasible, even factoring in government or utility subsidies and creative financing schemes that can lower the initial outlay.

“It’s a whole different ball game in the private sector,” says NAESCO President Donald Gilligan. “The average payback for public sector projects is figured at between 12 and 20 years, whereas in the private sector it’s 2½ years. There is growing pressure on private owners to make their buildings more efficient, but it’s more difficult to secure performance contracts there because of their shorter payback horizon.”

ESCOs know, however, that they’ll have to start changing minds in the private sector for the upper end of the broad market potential to be realized. The most recent LBNL industry study concluded that the private commercial building sector represents the single biggest raw opportunity for ESCOs. Worth anywhere from $14 to $34 billion overall, it displays the largest gap of any market sector between what’s been tapped so far (9%) and what’s available.

There’s evidence that ESCOs have been chipping away at the market, though, and that more inroads could be made. The LBNL study estimated that ESCO revenue from the sector increased almost one full percentage point between 2008 and 2011, reaching 8.1%. That could continue to rise as governmental entities and utilities ratchet up efforts to tackle the growing problem of energy-hogging buildings with more vigorous application of both carrots and sticks.

Gilligan points to growing efforts to establish energy efficiency benchmarks for private buildings as encouraging. By creating a relative scoring system for rating buildings on energy usage and requiring owners to make their property scores public, some cities, such as New York, are ratcheting up the pressure on property owners to cut back on energy usage — and for good reason. LBNL places the remaining annual blended energy savings potential of the private/commercial sector at between 128 and 188 trillion BTUs, 36% of the total across all market sectors, and by far the single largest.

“In the private market there’s always been an understanding that large, Class A office buildings drive peak loads in many areas,” Gilligan says. “So there’s more pressure from utilities and public policy makers to get building owners to make improvements.”

On the incentives side, more creative methods of helping the private market fund improvements are cropping up. Adams sees the potential for increased passage of property assessed clean energy (PACE) legislation in states to spur investment. It addresses one of the chief concerns commercial and industrial building owners have with how to pay for it by more closely linking improvements to the property’s long-term market value.

“In 30 or so states, ESCO work can be paid for with property tax assessments, keeping those expenses off the balance sheet,” Adams says. “The theory is that the building will be worth more with upgrades.”

Squeezing more from MUSH

The calculations are far different in the public sphere. ESCOs have made their livings in the so-called MUSH market — municipal/state government, universities, schools and health care — where the prospect of spreading out savings over a longer term is more palatable and can be justified as friendly to the public interest. While more mature, those markets still present strong growth opportunities as facilities age, indiscriminate energy usage is demonized, and more agencies are ordered to comply with stricter requirements governing the energy efficiency of buildings they occupy.

Representative of the push to bring more public facilities in line is the President’s Performance Contracting Challenge, says Larsen. It awards energy-savings performance contracts for federal facilities, and funds them with the recoupment of energy costs over an extended period. The contract cap for that program was doubled to $4 billion in 2014, ensuring that the federal sector will be a rich source of ESCO work in the years ahead.

“Many federal agencies have committed capital to the task of retrofitting federal facilities as part of this,” Larsen says. “The big driver for the program is the general age and condition of public facilities.”

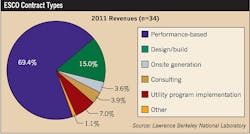

Public and institutional business accounted for some 85% of ESCO revenues in 2011, according to LBNL, and no amount of gain in commercial work is likely to unseat it in the near term. Within that sector, LBNL sees the largest slug of potential residing in the K-12 market ($16 to $29 billion), which has also been the richest vein of work over the past decade. The health care/hospital market, relatively untapped, has a similar worth — $15 to $26 billion. Comparatively fewer opportunities remain in the state, local, and federal government, university, and public housing markets, although less than half of what’s available in each has been realized.

While the prospect of energy savings will continue to drive the ESCO business, a growing number of projects in the public sphere will be structured to have additional components that aren’t directly tied to energy reduction. The ability to sell ESCO projects partly on their ability to generate money to pay for other pressing improvements could be a wild card in determining how fast and how much the ESCO industry will grow. But the all-important concept of “payback” poses one of the biggest challenges the industry faces.

“One of the big open questions in the ESCO industry is that there are no standards or protocols in place for some of these non-energy benefits — of how you measure operations and maintenance project savings,” Larsen says. “It’s unclear at what point we’re going to see standards developed for how to quantify or monetize non-energy savings.”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR: NECA Tool Aims to Grease EC Path into Energy Services

Long relegated to being subcontractors in the growing energy services market, electrical contractors are spying opportunities to edge into a more primary and potentially rewarding role. A program offered by the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA) is taking shape to help contractors stake out ground long held by traditional energy service companies (ESCOs).

Unveiled early last year, the online-based NECA Energy Conservation and Performance (ECAP) tool gives member contractors a one-stop resource for calculating and compiling the optimal financing and performance guarantee elements needed to develop comprehensive energy service proposals.

Incorporating the services of three partner companies, ECAP was conceived as a way to help contractors new to the energy services business navigate the complex, but essential, process of designing tailored and viable proposals they can bring to prospective clients. It addresses some of the formidable barriers electrical contractors face in trying to replicate the services that well-established ESCOs can readily provide.

“The obstacle for many small- and medium-sized contractors is developing the relationships needed to offer energy services,” says Mir Mustafa, NECA’s executive director of business development. “When they try to do this work, they often run into situations where banks won’t finance these kinds of jobs. Then they’re in the bad position of having to go back to a customer and tell them they can’t do it.”

Using the ECAP tool, he says, electrical contractors can aggressively solicit energy service business knowing they can directly address client concerns about payback, financing, and guarantees for energy efficiency projects. Moreover, it has the potential to put more power in the hands of electrical contractors vying for energy service business.

“Traditional ESCOs get a 30% to 40% margin on this type of work, and their subs get a small cut of that,” says Mustafa. “One of the benefits of ECAP is that it enables contractors to become energy solutions companies themselves.”

Walton Electric Corp., Upland, Calif., is one of some 150 NECA members that have registered to use ECAP. Ty Gray, who works in business development and technology management for the company, says ECAP has given Walton an avenue to probe the energy services market more deeply. The company has done some work in the area, but chiefly as a subcontractor — given the difficulties of structuring projects from scratch.

“Now, when we engage with clients on standard tenant improvement work, for instance, we can have a secondary conversation about work they hadn’t even considered due to budget constraints,” Gray says.

With the ability to structure verifiable and guaranteed efficiency upgrade projects that produce ongoing savings, Walton can propose an expanded scope of facility upgrade work that the energy savings can help fund, Gray says.

“With one client we were able to use ECAP to ultimately provide an LED lighting upgrade, an HVAC chiller improvement, and exterior windows all at one time, with Walton handling all aspects of getting that work done,” he says.

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].