Key Takeaways

- Community solar is projected to contract by about 8% annually through 2030, mainly due to funding reductions and market saturation.

- Smaller, urban-focused projects are easier to implement and connect to existing grids, making them attractive for dense neighborhoods and renters.

- Utility and state policies significantly influence market growth, with some states experiencing rapid development while others face utility opposition and regulatory hurdles.

- The market is fragmented, with top developers controlling around 20% of capacity, and rural co-ops exploring community solar as a cost-effective alternative to rooftop solar.

- Regulatory delays, especially in states like New York and California, impact project timelines, emphasizing the need for streamlined interconnection processes and supportive legislation.

Tomorrow the sun will come up. For community solar developers, that’s about all they can count on these days. Between federal funding pullbacks, state roadblocks, and a handful of saturated markets, the community solar market is on track to contract by an average of 8% annually through 2030, according to the analyst firm Wood Mackenzie.

In some respects, community solar should be easier to implement than utility-scale solar farms, which span hundreds of acres apiece. As EC&M explored in a February 2024 article, “Demand for New Solar Farms Soars,” utility-scale projects struggle to overcome community pushback regarding their environmental impact, property value effects, and potential impacts on arable land.

Community solar systems typically are smaller, which makes it easier to find room for them in urban and suburban areas. Those places are also home to potential customers who want rooftop solar but can’t have it for reasons such as cost, foliage, HOA restrictions, or because they’re renters.

“The community solar value proposition makes so much sense for dense neighborhoods, apartment dwellers, places where there may even be warehouse space or public parking that’s available,” says Barry Cinnamon, CEO of San Francisco-based Cinnamon Energy Systems.

Another big challenge with utility-scale projects is getting power to market. That’s less of a hurdle for community projects because they’re physically smaller and therefore closer to existing grid interconnections. Community systems average 5MW for ground installations and a megawatt or two for rooftops, which is easier for congested grids to accommodate.

“It definitely is still a key challenge for community scale, but it’s much less of a hurdle than it is for utility scale,” says Caitlin Connelly, Wood Mackenzie research analyst. “It’s about equivalent to what maybe you would see for a commercial and industrial (CNI) project. Rooftop [community solar] systems especially have a much easier time interconnecting. They’re usually connected to the distribution grid, so they don’t have to go into lengthy transmission studies.”

Scale also affects the types of contractors serving the community solar market.

“It’s not utility scale because you’re not talking about a 20MW system,” Cinnamon says. “It’s more on the order of a megawatt or two or three, and that’s well within the range of most commercial solar installers. Whether it’s put on top of a parking lot or apartment buildings or a warehouse, those are basically commercial-size installations.”

The role of utilities

There are a variety of community solar business models and developer types.

“The [community solar project type] that I work with mostly is the traditional model enabled by state legislation,” Connelly says. “That’s either a utility-led program or a state-run program enabling third-party developers. There are other community solar models that are customer or neighborhood-driven through CCAs or municipal utilities. Another thing that we see a lot is utility-driven programs focused on low-income customers that are community-scale. I think there are several hundred players in the market, but the top five community solar developers represent around 20% of the capacity installed in 2024. So it’s a very fragmented market in the long tail, but in terms of top players, it’s pretty consolidated.”

Some rural co-ops offer community solar, such as Citizens Electric in southeast Missouri.

“It’s been a pretty successful program,” says J.W. Hackworth, manager of member services. “I think it’ll probably even get more traction and more interest as [residential] tax credits and things like that sunset. We [often get] asked about rooftop solar and how it compares to our shared solar program. If the tax credits and all that go away, it’s a better value instead of putting panels on your roof.”

Its two farms — roughly 750kW apiece — are owned by Wabash Valley Power Alliance, which was Citizens’ generation and transmission provider until 2025.

“We’re just an off-taker of those facilities now,” Hackworth says. “Citizens is at this unique crossroads because we’re going to stand up our own power supply. Will it be community solar? Will it be some sort of additional generation asset? I don’t know. We haven’t done any evaluation to do any sort of community solar beyond what Wabash built here.”

Citizens Electric is among several Missouri utilities that offer community solar programs, including municipal ones such as City of Columbia Utilities and investor-owned ones such as Ameren.

“We are trying to get all the utilities to do it,” says James Owen, executive director of Renew Missouri, a lobbyist group focused on solar and wind. “We think, from the perspective of a utility-owned solar subscription program, that’s a good way for them to serve their customers’ demand for clean energy.”

An HOA also could create its own community solar program, such as a country subdivision or rural town in a wildfire-prone area where transmission lines frequently are at risk.

“The most questions I get are for people who don’t want to do it just for their house; they want to do it for a neighborhood,” Owen told EC&M in a November 2022 article, “Rise in Off-Grid Residential Solar Installations.” “In Missouri, if it’s not connected to the grid, there’s very little, if any, regulation of that. There was a case in front of the Public Service Commission where a group from Saint James wanted to get permission to do this. The PSC said: ‘You don’t need permission from us. You’re not a utility. You’re not selling this to the public.’”

Slow growth ahead

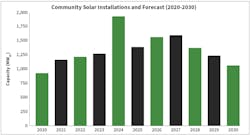

At a national level, community solar installations grew steadily between 2000 and 2023. In 2024, they spiked as developers scrambled to get projects online ahead of whatever changes a new president might bring. One example is the EPA’s August 2025 cancellation of a $7 billion grant program that included money for community solar. In Q3 2025, they totaled 267MW in Q3 2025, according to the December 2025 “US Solar Market Insight,” a quarterly report series from Wood Mackenzie and the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). For perspective, commercial and residential installations in Q3 totaled 554MW and 1,088MW, respectively. See the Chart below for the forecast for community solar installations through 2030.

That’s a 21% decline compared to Q3 2024, but six states bucked that trend. In fact, two of them — Illinois and New York — accounted for 68% of all new Q3 2025 capacity. That’s also an example of how the market opportunity for electrical contractors and design firms varies dramatically by geography.

“2024 was a huge year for community solar that was driven by only a few top state markets — New York, Illinois, and Maine — as well as some growing momentum and a few of the less mature state markets,” says Connelly, who writes the “US Solar Market Insight.” “Maine had a particularly strong 2024 because it was transitioning into a new tariff mechanism for compensating for these solar projects. That expired in December 2024, so a lot of projects were rushing construction, trying to get as much capacity online. That really added to that uptick.”

Those mad dashes were followed by a relatively slow 2025.

“Those mature, very big community solar markets — like New York, Massachusetts, Minnesota — we’re seeing them reach a sort of saturation point where growth is stagnating,” Connelly says. “The bright side is that the pipeline for projects under development in existing state markets is very large. Even in markets where we’ve seen very slow buildout in terms of capacity coming online — like New Jersey, Maryland, Massachusetts — they’re very active in terms of projects that are under construction or in late-stage development. Illinois, especially, will continue to be very strong throughout the next couple of years.”

California has a reputation for being a leader in renewables — except when it comes to community solar.

“When you look at the statistics ranking different states for their adoption of community solar, you’ll see some doing really well, [such as] Minnesota,” Cinnamon says. “And you see others where there’s tremendous potential, like California, where community solar barely even registers. You kind of scratch your head and say, ‘What’s the problem?’ I feel bad for the community solar developers who hope that California’s going to change.”

A major reason is utility opposition. “California utilities realize that they will lose profits [with] more community solar,” Cinnamon says. “They’re really, really good at lobbying the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). Then Governor Newsom came in and really started to come down hard against independent solar and pushing utility-scale, and the situation got even worse. Until the attitude of the CPUC changes — where they’re actually going to regulate the utilities on the dimension of low ratepayer costs and making sure that underserved communities have local solar because they normally can’t put a lot of solar on the roof — the California market is going to be in hibernation.”

The outlook is somewhat brighter in the middle of the country.

“Especially for traditional community solar, there’s been some pushback and difficulty creating new programs in Ohio or other states in the Midwest,” Connelly says. “But there is a lot of bipartisan support because of their job creation and because these are smaller than utility-scale. So their development timelines are a lot faster than you would see for giant utility-scale projects. They’re also providing direct bill discount savings for customers. So all of those are very attractive to not just community solar developers or contractors or other stakeholders but also policymakers and customers.”

One example is Missouri, where a 2025 bill would have required every retail electric supplier to implement a community solar pilot program from 2026 to 2028 and continue operating until total demand equaled 5% of its sales for the previous year. Each community solar facility would have been required to have at least 10% low-income customers and 20% residential customers.

The bill — which never got out of committee — also provided some high-level interconnection requirements, such as applying net-metering standards to community solar facilities under

100kW. That’s noteworthy because interconnection is another aspect that varies by market, with lead times increasing in some states over the past few years.

“New York, which has a hugely successful community solar program, has seen development timelines nearly double in the last four years,” Connelly says. “That’s driven by the number of applications that the program receives. And then adding things like interconnection studies, it is a lengthy process, like four years.”

Streamlining and expediting that process is one more way that regulators and legislators could help.

“Everything I hear from utility companies, utility regulators, lawmakers, analysts is: ‘We need more power. We need more sources of power. ‘We need to figure out how we’re going to deal with the demands of the grid,’” says Renew Missouri’s Owen. “But all I’m seeing is limitations on what is going on to the grid and what customers can take advantage of. Instead of eliminating people’s options, we should be expanding them, and the law should be addressing that. And right now, I think the law is falling behind.”

Half a continent away, Cinnamon has a similar lament.

“I’m very supportive of it,” he says. “I’m just so jaded about 15 years of seeing what happens in California. It really never seems to go anywhere.”

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].